June Aochi Berk, now 92, was 10 when her family was taken from its home after the Pearl Harbor attack

By Barbara Burke

Special to The Malibu Times

“I was just 10 years old when my family and I were ordered to get on buses, and we didn’t even know where we were going or for how long,” said June Aochi Berk, 92, who was born in the Hollywood District and is a survivor of America’s forcible relocation and incarceration of more than 125,000 Japanese residents from western states during World War II.

Berk spoke at Malibu United Methodist Church at a March 2 event sponsored by the Malibu chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

She discussed her family’s evacuation after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, following the Dec. 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor. The order directed the U.S. Secretary of War to “prescribe military areas … from which any or all persons may be excluded.” Acting under that authority, Gen. John DeWitt arranged the forcible removal of Japanese Americans, including those who were U.S. citizens by birth, such as Berk, and their Japanese immigrant parents from their West Coast homes and communities.

“Our family first went to Santa Anita where we were housed in horse stalls,” Berk said, referring to Arcadia’s racetrack. Displaying a picture of her visit back to the horse stalls a few years ago, Berk commented, “I was amazed at how small the stalls were and by the fact that our family of five slept together in one stall — we were given empty white pillow cases and told to fill them with straw — that’s what we slept on.”

Attendees sighed, expressing disbelief. Even when viewed through the prism of history, they found it difficult to comprehend that those events happened in America.

Moderating the conversation with Berk, UCLA Adjunct Professor of History Susan H. Kamei, author of “When Can We Go Back to America? Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II,” explained that euphemisms were used to mask the underlying motivation for the evacuation, which was grounded on discrimination against Japanese Americans that had been increasing for many decades.

“The fact that there was longstanding discrimination against the Japanese is demonstrated that by nightfall on the day of Pearl Harbor, more than 2,000 men in their community were arrested, despite having committed no crimes,” Kamei stated. “Their passports were confiscated, and they became illegal aliens.”

Kamei displayed a picture of the FBI searching her family’s home on the evening of the Pearl Harbor attack.

“The officers went through our entire house,” she said, displaying a black-and-white picture of the search. “They thought we were guilty — guilty by ancestry.”

Kamei elaborated: “Even before the declaration of war in 1941, agricultural and labor groups wanted to remove Japanese Americans.”

Reflecting, she said, “Throughout American history, immigration and naturalization have been politically contentious topics, ever since 1790 when two Congressmen got into a duel on the floor of Congress discussing the topic.”

Audience members leaned in to see the image of two pugilist lawmakers who lost control when debating the Nationality Act of 1790, the first law to address eligibility for citizenship by naturalization. That law excluded people of Asian lineage from naturalizing.

Kamei noted that, throughout American history, as subsequent waves of immigrants arrived on our shores from various countries — the French, the Irish, the German, the Chinese, and then, the Japanese, all immigrants were subjected to discrimination.

“Pearl Harbor lit the powder keg, resulting in the internment of those of Japanese descent on the West Coast,” Kamei stated. “We say that June and her family, my parents, and others were incarcerated — we do not use the term internment.”

The word “internment” is a term of art in the international law of war and does not correctly describe the community-wide incarceration that Berk and Kamei’s parents and others living in western states endured. Instead, “internment” invokes an internationally agreed legal scheme under which a warring country may incarcerate enemy soldiers and select civilians who are subjects of an enemy power.

Readers may be interested in reading “Americans’ Misuse of ‘Internment,’” by Yoshinori H.T. Himel in this regard.

“My Dad came to the U.S. in 1899, when he was only 20 years old,” Berk said. “He worked on the railroad tracks for two years, went to Washington state for a few years, and finally, he came to Los Angeles, where he operated a business at Sunset and Vine. He had a Japanese workers employment agency and was one of the first gardeners in Hollywood.”

Berk’s mother arrived in America in 1924, just before Congress banned immigration from Japan, with limited exceptions.

“From 1924 to 1952, those of Japanese descent who lived in America were required to maintain a registration.” Kamei stated, as the registration signed by Berk’s father was shown on the screen.

Berk explained in detail that even before WWII, those of Japanese descent were not honored equally with others residing in our country.

Simply stated, in that era, they were not included in America’s multi-cultural tapestry contemplated by the concept embodied in the preface to the U.S. Constitution, which states “We the People.”

“We couldn’t obtain citizenship,” Berk stated. “My first brother died from pneumonia because back in those days, we couldn’t go to the hospital. We couldn’t own land, and we could only rent properties for three years, so we moved around a lot.”

Berk also shared some more pleasant details of her childhood before being evacuated.

“We had a small community of Japanese businesses, some boarding houses, and shops,” She said. “I had a love of Japanese dancing from when I was a small child and we performed in a 400-seat theater that was on the second floor of a building that housed a gambling area on the third floor and a shop on the bottom level. We even danced at the Hollywood Bowl.”

Images of a small and beautifully-attired Berk amidst a troupe of dancers displayed on the screen.

“I was fortunate enough to be taught by Fujima Kansuma, a master kabuki teacher,” Berk said.

Her next remark, “My Dad and Mom were frustrated Kabuki actors!,” elicited laughter from the audience.

Berk’s enjoyable and peaceful childhood was abruptly interrupted by the evacuation order.

“All of a sudden, there were notices posted on the telephone poles,” she said. “Most people, including my father, had to quit working because we couldn’t travel more than 5 miles from our home. I remember having big bonfires because everyone in the community was burning pictures, books, even China — anything that had Japanese writing.”

There were closing sales at stores in her community, she added.

“However, throughout this whole experience, there were so many kindnesses extended to us,” Berk said. “Our postman said he would take care of our belongings and, when we were in the camps, groups of Quakers and other groups, including the American Baptists, the Methodists and Presbyterians, brought us cookies and sent Christmas gifts for us. They also helped the teenagers, including my sister and brother, arrange for colleges to attend and for places to work in the other states that were not affected by the evacuation.”

When she received her Christmas gifts, Berk said, “I remember thinking, there’s people on the outside thinking of us?”

Kodomo no tame ni – For the sake of the children

Dignified and determined, the incarcerated adults focused on their children having as usual a life as possible, Berk noted, explaining that they never cried in front of the children or showed any frustration.

“’Kodomo no tame ni’ — For the sake of the children — is a very strong principle in our culture.” Berk said. “There’s another principle, that one should never give up her dignity and should not show she is defeated, is also very important and that is why all the adults boarding the evacuation buses were dressed up as if they were going to attend a church service.”

Life at Santa Anita was spartan and scary, Berk said. Soon, the family was relocated by the War Relocation Authority to Arkansas. There, they endured some flooding and deteriorated conditions.

“They wouldn’t let any Japanese schools in the centers,” Berk said. “However, they did let the children perform dances because it made the older incarcerees happy.”

Berk talked about a lovely picture that attendees viewed on the screen.

“The fathers painted the wall of the stage and the mothers hung flowers from the ceiling and made our costumes,” she said. “We performed often in the camps.”

The kimono her mother made for her is now housed in the Japanese-American National Museum in Little Tokyo.

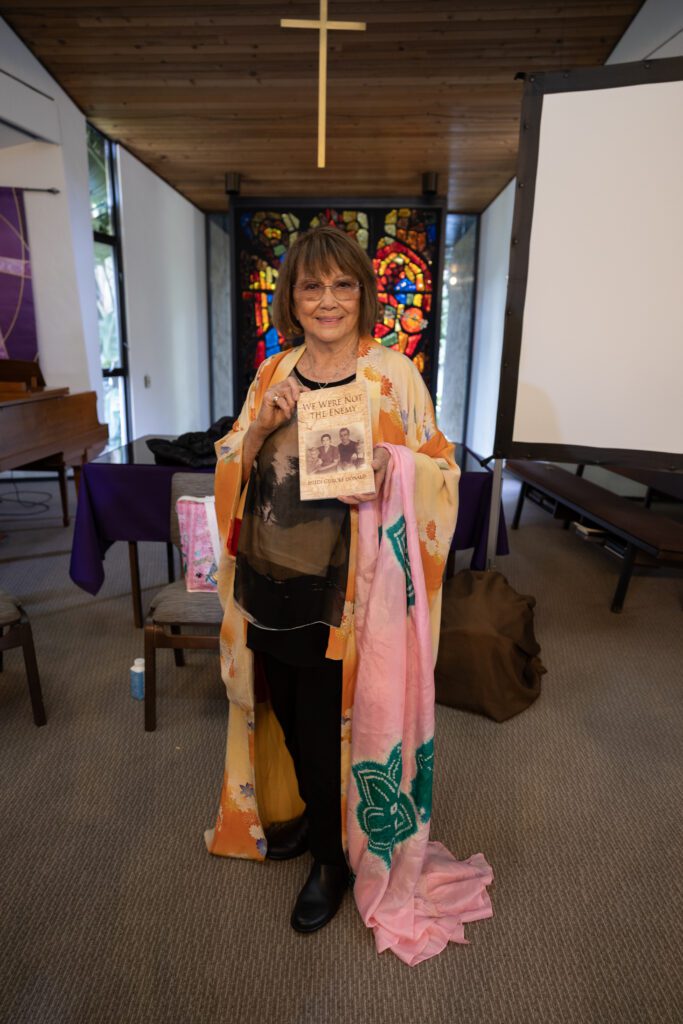

Holding up a gorgeous yellow kimono, Berk said, “Just a few weeks ago, I found this kimono at the very bottom of one of the two suitcases my mother packed for me to be evacuated. This one is one my mother got from Japan.”

The audience was enthralled with an image of Berk stamping the Ireichō, which the museum’s website describes as “a sacred book that records the names of the more than 125,000 persons who were unjustly imprisoned in U.S. Army, Department of Justice, and War Relocation Authority camps during World War II.”

Berk’s message was difficult as she recounted her internment. However, her discussion about her life after being released from internment was quite joyful. Initially, her family members were given $25 each and a bus ticket to Denver where they established a business. They could not return to California for a few years. They finally relocated to Los Angeles in 1953.

The pair displayed a gorgeous image of a newspaper photo of Berk in 1954 when she was one of the top five candidates for the title of the beauty queen of Nisei Week, an annual Japanese festival in LA.

“That launched her modeling career,” Kamei said, adding that Berk is a leading ambassador for the Japanese American community.

“If you want to learn more about me, you can see the exhibit at the museum that allows attendees with iPads to feel as if they are walking along in a simulation of our boarding the evacuation buses,” Berk said. “In the artificial intelligence exhibit, I do a Japanese dance and soon, you’ll be able to ask my hologram questions as well!”

In closing her discussion, Berk addressed what everyone should glean from the Japanese internment experience. She admonished, “We all need to be very careful because, with just a signature or the passing of a law, we can lose our constitutional rights! If one person’s freedom is taken away, it’s a communal loss.”