By Lance Simmens

I can say with all sincerity that Jimmy Carter was a profound influence in my life. As a child of the ’60s too young to attend Woodstock (I only turned 16 the week the Happening happened, therefore still without a driver’s license) and lucky enough to narrowly avoid getting drafted (thus putting to rest the difficult decision as to whether to move to Canada or Sweden), my political maturation took form during the early ’70s as the political corruption of Watergate and the domestic upheaval over our withdrawal from Vietnam set the stage for reform of our political system.

As fate would have it, I was recovering from a serious accident that left me with a broken neck in January 1973. It necessitated several surgeries, absence from college for two quarters, and a healing process that left me in an upper body cast for the summer. I spent my convalescence enthralled by the daily political drama known as the Watergate Committee hearings, which unfurled the deep underbelly of a corrupt political system in need of serious surgery. I studiously watched every minute of the Watergate hearings that summer and jettisoned my dreams to be a professional baseball player.

While recuperating in preparation for a return to college in Georgia, I found that my passion for politics and public policy grew exponentially, and I excitedly declared political science as my major upon returning to classes. I excelled in academics over the next several years and in January 1976, I was selected by the political science department to represent the school as a candidate for an internship in the Georgia State Senate in Atlanta. I was chosen for the program, and since the Legislature is in session for three months out of the year, I would complete my Bachelor’sdegree serving in the State Senate.

I secured a room in a fraternity house on the Georgia Tech campus through the woman I was dating at the time and immersed myself in the opportunity that had presented itself with all the vigor of a soul who had discovered his lifelong professional passion: namely to devote his professional career to helping those less fortunate through the development and implementation of public policy.

As I made acquaintances in the Capitol, I would be introduced to statesmen such as State Senators Pierre Howard from Decatur, and Julian Bond from Atlanta. Soon, the three of us would be engaged in serious political discussions over lunch in the state government cafeteria across the street from the Capitol several days each week. Bond introduced me to comedian/activist Dick Gregory, who was visiting the Capitol, and we would end up having dinner that evening. It was an education that the classroom simply cannot match.

Several weeks into my stay, I was asked if I was interested in flying to New Hampshire with a group of the so-called Peanut Brigade folks from Georgia who would be canvassing the streets of Nashua knocking on doors with a former governor and peanut farmer from Plains, Georgia, who had decided to run for president. A relative unknown nationally, Jimmy Carter decided that through honesty, integrity, and abject seriousness, the nation needed to find its way out of the swamp of corruption that Watergate had uncovered.

I enthusiastically jumped at the offer, and there I was tramping through the slushy streets of Nashua knocking on doors in the freezing cold New Hampshire winter, as the candidate and nearly a dozen other candidates hopscotched through the streets, also knocking on doors, and assiduously avoiding literally running into each other in what had become known as the paragon of retail politics: namely, the first primary of the 1976 presidential election.

In the evenings, we would all gather at the famous Wayfarer Hotel, where in adjoining booths sat famous news commentators such as Douglas Piker, Tom Brokaw, John Chancellor, and a cast of others. For this 22-year-old novice to politics, I found an excitement that stays with me to this day.

Over the next several months, I would find myself in Jacksonville, Florida; the Bronx and White Plains, New York; Bucks County, Pennsylvania; Gary, Indiana; Livonia, East Lansing, Ypsilanti, and Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Sioux Falls and Aberdeen, South Dakota. Along the way, I had the honor and privilege of attending an AME church service in Mt. Vernon, New York, where Martin Luther King Sr. was giving a sermon. I was one of three white people in that glorious explosion of celebratory redemption that was a ceremony so distinctly different from the solemn Latin, incense-filled experiences I participated in as an altar boy in a Catholic Church in northeast Philadelphia. And there we sat, taking it all in, me, Pierre Howard, and Deputy Mayor Tom O’Toole, from neighboring New Rochelle, New York.Since the campaign frowned upon us wasting expenses on hotel rooms, we stayed in people’s houses, and in New Yorkthe deputy mayor and his wife were more than amiable hosts during our short visit. It was, needless to say, an exhilarating experience and, lo and behold, although we got trounced in the New York primary, we won the nomination.

By summer, I had graduated from college and found my way to the Democratic National Convention in New York City. I had arranged to stay with a friend of mine in the city and was assigned to handle credentials, and I believe the official title on my ID was floor manager. So each day I would be outfitted with a large batch of credentials, ranging from nosebleed seats to floor and press passes. Needless to say, I was a very popular person, and many of the elected officials and others whom I had met along the way to the nomination sought me out for the highly prized packet of credentials tucked into the only suit coat I owned. Being a part of a national political convention is both exciting and exhausting,but by all accounts, a choreographing nightmare. I have worked on the podium for 10 of the last 13 conventions and spent quality time with far too many celebrities and political stars than I can mention, but it all started in 1976.

That fall I had secured a graduate fellowship at Temple University, where my responsibilities during a two-year Master’s program would be to do research for a mentoring professor and teaching American government courses.However, I simply could not abandon the presidential campaign and incorporated into my schedule running the 8th Congressional District campaign office in suburban Bucks County during the fall of ’76.

We won. I stayed in school while all my colleagues flocked to D.C. to find jobs in the Carter Administration. I did make my way to Washington to participate in the Inauguration and several inaugural balls that evening. It was a frigid day and not owning a proper coat, I nearly froze while attending the event that was held on the East side of the Capitol. I resisted the urge to look for a political appointment and devoted the next two years to securing a post-graduate credential.

In the fall of 1978, armed with a Master’s degree in public administration, I made my way to D.C. to start what would become a nearly 40-year immersion in politics and public policy. I spent a couple of months on Capitol Hill working for Georgia Sen. Herman Talmadge (our politics were diametrically opposed to one another, yet I paid the dues of getting some Hill experience) and finally secured a position in the Department of Housing and Urban Development as a congressional affairs specialist. I worked directly out of Secretary Moon Landrieu’s office and learned the heartbreak that would accompany defeat at the polls in 1980. But my Washington experiment was only beginning and would last over 22 years.

I would end up working for two presidential administrations, two U.S. senators, two governors, the U.S. Senate Budget Committee, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, and the President’s Commission on Y2K Conversion.

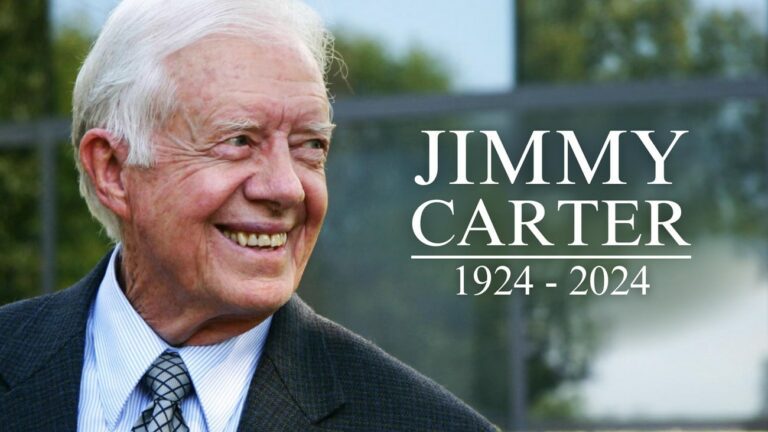

My life has revolved around trying to fulfill the virtues that Jimmy Carter instilled upon those of us who worked on his campaign: namely, honesty, integrity, and the desire to help those who are most vulnerable in our society. Immediately preceding Carter’s term, the nation had fallen into a deep dark place: the blunder in Vietnam, the corruption of Watergate, the questioning of our values and what we as a nation stood for. Carter helped bring back a wholesomeness to our political system. To this day, I value the role that public service can play in enriching other people’s lives. Carter never stopped trying to make this world a better place and provided a level of inspiration that has been invaluable to all who came within his orbit.

As a writer, I can only marvel at the body of work he has contributed, seemingly on a yearly basis. I am aware of 27 books that he has authored, I suppose that this is a conservative number, but amazing nevertheless. Carter put his words into action. The Habitat For Humanity project has touched more than 70 countries and has helped more than 39 million people improve their living conditions since 1976.

In 2002, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Over 99 years, he has enriched the lives of others. Until recently, he would teach bible studies to children in the Marantha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia. For nearly a century on this Earth he has been an indefatigable example of goodness, compassion, and kindness, all virtues that make the world a better place.

To me, Jimmy Carter was an inspirational figure in my life. He showed that one can actually accomplish and teach valuable lessons to individuals and communities that he has served in a life where nothing ever stood still. During the 1976 campaign, I would greet him curbside at events in cities spanning across the primary landscape. He always had a smile, a large grin, and he always wanted to know how I was doing before he would ask what are we about to do here.

While serving one term as president, he accomplished much that revolved around peace; the Camp David accords in 1978 between Egypt and Israel, which would lead to a peace treaty the following year, stand out as a huge measure of his commitment to peaceful co-existence.

I was privileged to be at the right place at the right time. More importantly, I was able to realize it. Carter was the right person at the right time in our history, and as often happens it is not recognized until long afterwards. Upon his passing, I have heard some describe him as the best ex-president the country has ever seen. I think he would just grin that grin of his. Carter never stopped trying to make a difference, and never yielded to the temptations that would have you slow down. Never gave up. Now you can rest in peace. It was a pleasure knowing you and working for you. Thank you.