Last week, The Malibu Times explored the trend of financially unsustainable retirement spending in California, and how such spending contributed to the bankruptcy of cities such as San Bernardino and Stockton.

In the second of a multipart series, we examine the City of Malibu’s pension obligations, and what those obligations are projected to be in the future.

The City of Malibu does not have its own fire or police department, which have been a principal driver of retirement costs for many cities. The city does contract each year for police services with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, including a $6.3 million payment in Fiscal Year 2011-12.

Furthermore, as it incorporated as a city only in 1991, Malibu only has 11 retired workers collecting pension benefits. However, the projected costs are expected to rise in coming years and the issue will be worth keeping an eye on.

CalPERS

The City of Malibu, like many cities in California, contracts its pension system through CalPERS—the California Public Employees’ Retirement System. In Fiscal Year 2011-12 CalPERS managed retirement accounts for more than 1.6 million California public employees, receiving more than $11 billion from employees and cities in that time.

CalPERS is essentially a massive investment agency that collects pension pool payments and invests the money hoping to garner strong returns. The better CalPERS does in investment returns, the less individual cities have to pay in annually to the system. In addition to most cities, CalPERS handles investments for state employees and many counties.

Before the 2008 financial downturn, CalPERS reported net returns of $5 billion, $24 billion, $21 billion, $22 billion and $41 billion between 2002-2007, and had a reputation for being a very successful investment manager. But during the 2007-2008 and 2008-2009 fiscal years, CalPERS lost $69 billion combined. Returns have since picked up and CalPERS was always considered to be on solid financial footing due to the vast financial reserve the agency accumulated over several decades and its professional management.

“As the nation’s largest public pension fund with assets totaling $243.2 billion as of September 30, 2012, CalPERS investments span domestic and international markets,” according to the CalPERS website.

Malibu City Manager Jim Thorsen and Assistant City Manager Reva Feldman have both expressed faith in CalPERS’ financial strength.

“If CalPERS were to stop receiving payments from all the cities it collects from, I’ve been told it could still survive for 20 years,” Thorsen said at a meeting of the city’s Administration and Finance subcommittee in September.

How CalPERS works for Malibu

In order to qualify for CalPERS retirement benefits with the City of Malibu, a full-time city employee has to “vest,” or accumulate, five years of work for the city.

The city’s current employees work under a “2% at 55” plan, although that will change somewhat next year after new legislation signed in September.

“You get a pension of 2 percent of your highest average salary over three consecutive years when you turn 55,” Assistant City Manager Reva Feldman said in recent interview with The Malibu Times.

City workers can also opt to continue working until age 63, and retire with 2.4 percent of their highest salary averaged over three years, Feldman said.

CalPERS averages out an employee’s salary over the three consecutive years when they earned the most money.

Employees who have vested at least five years can retire before age 55, but receive a lower percentage of their highest average salary.

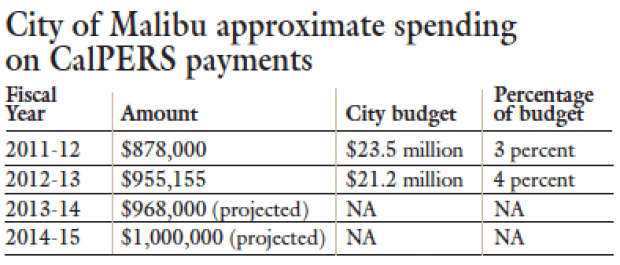

City expenditures on pension funds

Under this system, CalPERS calculates two percentages known as the employer contribution and the employee contribution. Employer and employee are obligated to pay a percentage of their salary into their pension fund each month. Malibu’s employer contribution is 11 percent for the 2012- 2013 fiscal year and the employee contribution is 7 percent.

The City of Malibu, like many other cities, covers both the employee and employer contribution for a total of 18 percent. Not all cities pay both contributions, though. If the City of Malibu faced a financial crisis or foresaw financial trouble, Feldman said the city could begin requiring employees to cover their own employee retirement contribution.

The employer rate fluctuates year-to-year depending on how well CalPERS’ investment pool does in the stock market, and in other investments.

“Employer contributions decline when investment returns rise and increase when investment returns decline,” according to a CalPERS handbook.

Two years ago, Feldman said the employer contribution rate was 12.3 percent.

One of the questions that has been raised in connection with this issue statewide is why cities and counties have been picking up the employee portion of the CalPERS payments.

For instance, CalPERS is similar to federal Social Security system, in which it is mandatory for employees to pay into the retirement fund. In 2012, the employee Social Security tax rate was 6.2 percent, while the Medicare tax rate was 1.45 percent.

Abuses

There have been a number of abuses of pension plans involving public employees reported in some cities and counties.

One controversial practice among non-CalPERS cities is called “pension spiking.” Some cities allowed employees to add unused sick and vacation hours to their final annual salary, thereby driving up their pension formula calculations in perpetuity.

In one well-publicized example, former Bell Police Chief Ryan Adams is currently in the midst of a lawsuit trying to keep the $510,000 pension he allegedly spiked after only working for the City of Bell for one year and making a $457,000 salary.

However, none of these practices apply to Malibu. CalPERS banned pension spiking in 1993. Malibu employees are eligible to “cash out” up to 192 hours, or 24 work days, worth of unused sick or vacation time, but those hours cannot go toward pension formula calculations, according to Feldman.