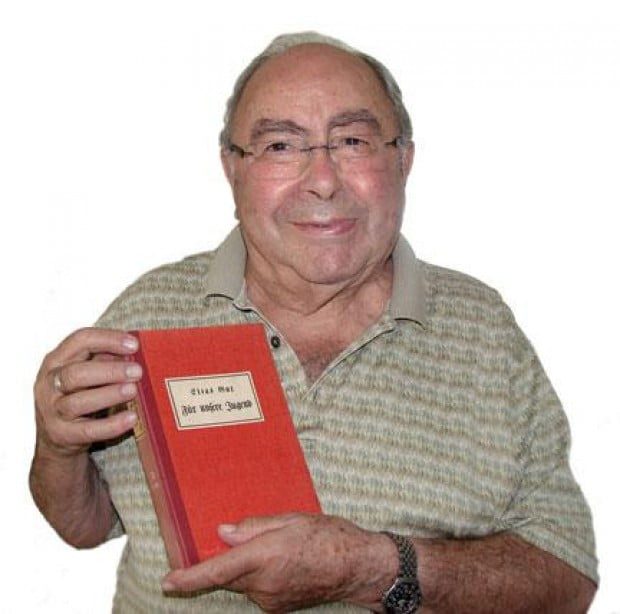

Having survived a concentration camp as a teenager, Walter Lachman came to America to build a new life. A part of his past was returned to him through a book he owned as a child, which was looted by the Nazis.

By Melonie Magruder / Special to The Malibu Times

When Malibu resident Deborah Valdez traveled to Germany recently to retrieve something that had once belonged to her father, she realized that musty old books sometimes have a value much greater than priceless artwork. The item she was claiming was an old collection of children’s fairy tales her father had last seen 67 years ago in Berlin, just before he and his grandmother were deported to a work camp by the Nazis.

“Once my father was identified as the original owner of this book that had been looted by the Nazis, the Berlin central library wanted to return it,” Valdez said two weeks ago in an interview with The Malibu Times. “It was part of their effort to repatriate items stolen from Jews during the war.”

Whereas the media has reported extensively in recent years on artwork looted by the Nazis in the years leading up to the Holocaust, little attention was paid to items like books until the curiosity of Detlef Bockenkamm, curator of Berlin’s Central and Regional Library, was piqued, according to a report in Spiegel Online International. Bockenkamm discovered that the thousands of books he has been collecting on these shelves were stored at the City Pawn Office in Berlin in the spring of 1943. The curator’s research proved that upward of 40,000 volumes in the Berlin city library alone had come from “the private libraries of evacuated Jews” and had been marked with an accession number, beginning with “J.”

The route that the book that was returned to Valdez’s father Walter Lachman is one of serendipity.

The article in Spiegel quoted a dedication in one 1921 edition housed at the Berlin library, titled “For Our Youth: A Book of Entertainment for Israelite Boys and Girls” that read, “For my dear Wolfgang Lachmann, in friendship, Chanuka 5698, December 1937.”

Rabbi Larry Seidman of Newport Beach read the online story and thought the name was similar to that of a friend who lived nearby and called him.

Lachman, who had changed his name when he arrived in America after the war, was floored. “That’s my book!” he said.

Wolfgang Lachmann was a young teenager, orphaned and living with his grandmother in what used to be East Berlin at the beginning of World War II. In 1942 they were arrested and deported to Kaiserwald work camp. He never saw his grandmother again.

In time, Lachman was transferred to the infamous Bergen-Belsen concentration camp where Anne Frank died.

“When the British liberated Bergen-Belsen, there were 13,000 dead people lying around the grounds,” Lachman said from his home in Laguna Nigel. “They just burned it to the ground because there was nothing else to do. Like thousands of other prisoners still there, I had typhus and I expected I would die too. But I survived.”

Lachman worked for a while as an interpreter for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration but came to America in 1946, landing in Springfield, Mass. He Anglicized his name. As soon as possible, he applied to become an American citizen, got his GED and earned a B.A. in Business Administration through night classes. He got married and worked for the dress shirt company Phillips-Van Heusen, where he eventually found his way to management before he bought a couple of the stores himself.

“America is the most wonderful country in the world,” Lachman said. “People don’t appreciate it. They don’t realize what evil is out there.”

Lachman attributes his amazing survival mentality to God looking after him and “a lot of luck.” When he learned of the discovery of his book, he made plans to travel to Berlin to recover it. But his wife of 54 years, Jean, was injured a couple of days before he was to leave, so he sent his daughter in his place.

“I had been to Berlin once with Dad about 10 years ago,” Valdez said. “He loves all things German. He took me to where he used to live and to the exact place where he was deported from back in 1942. They had a huge memorial with the names of everyone who had been deported from that site. Dad’s name was on it.”

Valdez found the ceremony prepared by the Berlin library officials for the book’s return to her father very moving.

“They found a suitcase belonging to one of the young girls who went to the camps,” Valdez said. “In it, she had a list of all her favorite books. She couldn’t bring the books with her because when they were deported they were told they could only bring one suitcase. So she made the list instead, and at the ceremony they read from portions of all the books. Philosophy, books about movie stars. They were trying to bring her to life for us. Art might be priceless, but librarians know how important books are.”

Lachman’s book was in remarkably good condition and Valdez was preparing to visit her father last week to return it to him. Rabbi Seidman said he is thrilled at the turn of events.

“I think the whole thing is a miraculous story,” Seidman said of the book’s journey. “It’s a real mitzvah.”

Lachman said he was “a little anxious” to see his book again, originally given to him by his Hebrew schoolteacher. Asked what he will do with it, he paused.

“Maybe I’ll read it again,” he said.