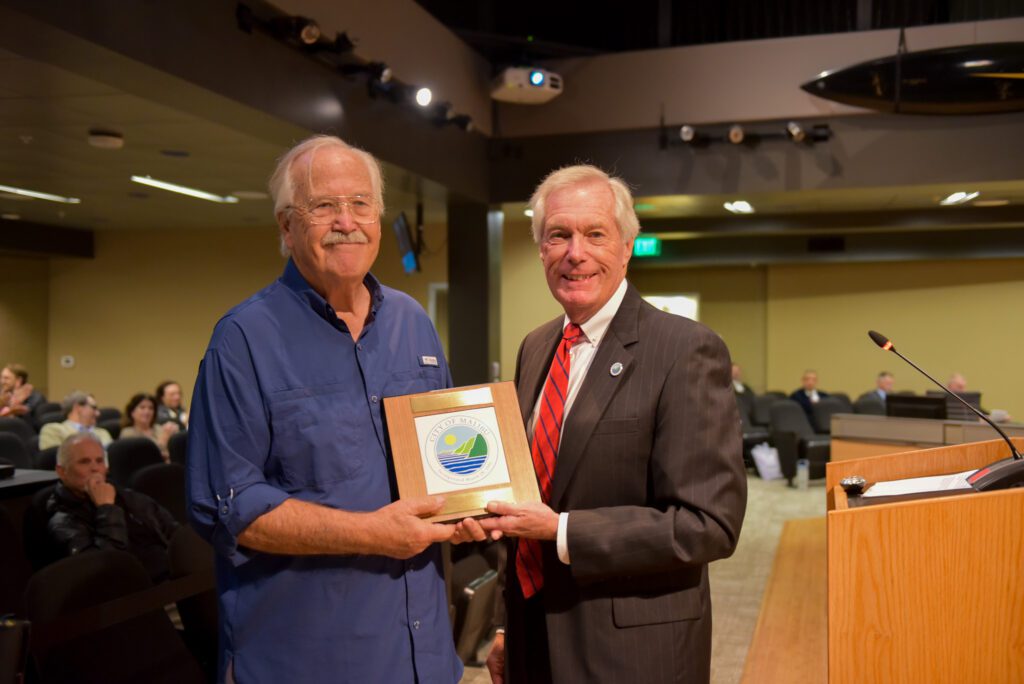

Jeff Jennings, an early Malibu mayor, to be honored at City Council meeting

The Malibu City Council is scheduled to give a big thank you to one of the city’s first mayors. Jeff Jennings will be honored for his three decades of public service to the community.

It was in 1992 that the now 50-year resident was elected to the council. He served three rotations as mayor until his term limits were up.

In 2008, Jennings was appointed to the Planning Commission by John Sibert, then asked to continue in the role by Lou La Monte and Karen Farrer. But when Doug Stewart was elected last year, Jennings said he would leave by the end of this year or when he turned 80, whichever came first. In November, Jennings became an octogenarian, so after a 15-year stint, he gave up his seat.

“It’s a stressful job,” Jennings said. “Plus, the fact that it’s time for me to make room for somebody else, for somebody in another generation to step up and make decisions. I felt it was time for me to move over.”

The Planning Commission has been under scrutiny recently by the California Fair Political Practices Commission, which is investigating possible conflicts of interest. While Jennings has not been accused of any conflicts of interest on the commission, he has often been the deciding vote in 3-2 majority decisions favoring development.

Jennings commented on Malibu’s Mission Statement, which in part reads that the city will “plan to preserve resources that contribute to Malibu’s special natural and rural setting” and also that “Malibu will maintain its rural character by establishing programs and policies that avoid suburbanization and commercialization of its natural and cultural resources.”

“The mission statement is in the preamble of the General Plan. Before I got on the City Council I was on the General Plan Taskforce that basically wrote all that,” Jennings said. “The problem comes in that the General Plan including the Mission Statement sets forth generally goals to be followed. It’s the job of the City Council to enact ordinances, legislation that carries out those goals.

“By the time it gets to the Planning Commission, our job is not to interpret things philosophically. Our job is to say, ‘does this project meet the requirements set forth in the ordinances?’ That’s where a lot of the debate comes from. When you get right down to it, the law is real clear. You apply the ordinances as they have been written, not the general scope or feeling of the way the General Plan was put together.”

He continued, “The law that requires cities to have a general plan also requires that they be updated periodically. You look at the General Plan and it describes, based in some neighborhoods, things that don’t exist anymore. Point Dume is a much different place now than it was when the General Plan was written. It might be time to have a new General Plan committee.”

Jennings expanded his comments in an email about the role of the Planning Commission “being simply to weigh a project against the standards established by the City Council in the zoning ordinances. My primary focus during my years on the PC was to try to make the process of building as predictable and consistent as reasonably possible. Architects should be able to know with a reasonable degree of certainty whether a particular proposal does or does not comply with the city’s standards. Members of the city’s Planning Department should be able to advise applicants based on the rules and on consistent interpretation of those rules. By the time a project reaches the PC, applicant(s) have already spent tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars and had the project examined and approved by every department in the city. That’s not to say there can’t be differences of opinion and city planning staff can make mistakes, but I resisted the idea that planning commissioners were free to bring in new subjective criteria or to change long-standing interpretations.”

Jennings himself is undergoing the long process of rebuilding his home that burned in the Woolsey Fire.

The public servant moved to Malibu in the 1970s so he could keep and ride horses and still be close enough to work in Los Angeles.

“It was a much different place,” he said. “Up in the hills it was a much more middle class community. There were lots of vacant lots. Over the years the area has become much more valuable economically. That has a lot of consequences. It’s expensive to build a house out here.”

The former litigator, who now practices estate planning law/wills and trusts in Malibu, got started volunteering in the late ’80s with the creation of Malibu High School. He hadn’t been involved in local politics, but married, had kids, and his wife said, “There’s this meeting you need to go to.” This next thing he knew, he was on a committee and lobbied the school board to create MHS. That led to his run for City Council at the urging of other residents.

“It’s really something that’s available to anybody who has the inclination and the time,” Jennings said about public service. “When you think about it, there aren’t that many people involved in city government in terms of the percentage of the population. Just about anybody with the interest can get involved and serve as I did. It’s a rare privilege really. I was happy to do it. I encourage people to participate.”