The neurologist Oliver Sacks, speaking last week at Santa Monica’s Aero Theatre about his new book on hallucinations, paused in the middle of an anecdote to ask if anyone else noticed that his microphone was echoing. The audience of about 200 people assured him it wasn’t. The 79-year-old Sacks reluctantly turned back to his microphone, then smiled. “So the shrieking lady will pass?”

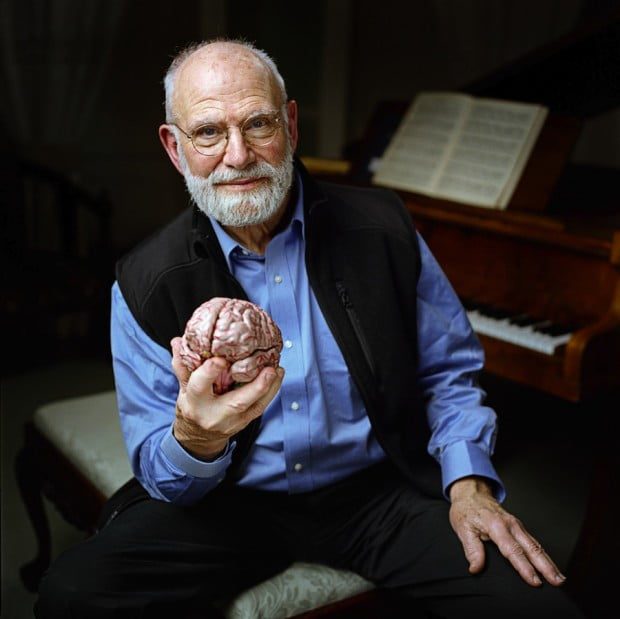

Sacks, a soft-spoken man whom the New York Times has called “the poet laureate of medicine,” has made a career of documenting the disorders of the brain. His 1973 book “Awakenings” chronicled his work with patients who lived for decades in frozen states, like human statues, in the chronic care Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx. Sacks recognized the patients as survivors of a pandemic called sleepy sickness that swept the world from 1916 to 1927. Through a then experimental drug called L-dopa, Sacks was able to virtually “restore” them to life, a story which was later retold in a 1990 film starring Robin Williams and Robert DeNiro.

He has written 12 books, including “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” “An Anthropologist on Mars,” and “Musicophilia.” The books often take the form of neurological case histories on conditions ranging from epilepsy to schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. He is also a practicing physician and professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine.

His latest, “Hallucinations,” is a series of case histories that tackles the subject of hallucinations in psychologically normal people. There are many different types of hallucinations, spread through 15 different chapters. Among these is Chapter Six, in which Sacks writes of hallucinations he personally experienced while living in Santa Monica and Topanga in the mid-1960s and experimenting with psychedelic drugs.

Part of Sacks’ reasoning in writing the book, he said, is de-stigmatizing hallucinations.

“Hallucinations [are] a delicate subject,” Sacks said. “The word often has ominous connotations. It suggests schizophrenia, dementia; at least it suggests this in the public mind and to some extent the medical mind, I think quite incorrectly. So people are often frightened of acknowledging hallucinations, even to themselves.”

People suf fering from schizophrenia suffer hallucinations directed at them, whereas the patients Sacks writes about in his book are often impartial participants in their hallucinations; they have no part in or control over them.

Hallucinations are much more commonplace than is widely believed, Sacks says, but those who experience them are unlikely to speak out due to the connotations with madness.

Many hallucinations are the brain’s way of compensating for lost faculties, he said, such as loss of sight or hearing. When one loses one faculty, the brain must remain active, so it compensates by “making up” sights, sounds or smells.

“People in Eastern dress”

The book begins with Sacks visiting a blind, 94-year-old woman in a retirement home. After having exemplary behavior for years, nurses said the woman was now seeing things and acting strangely.

“The first thing she said was, ‘I’ve seen nothing for five years, and now I’m seeing things…people in Eastern dress, marching in rows. And she spoke of animals, cats, dogs horses, children, tiny beings.”

The woman told Sacks the visions were nothing like dreaming. They were more akin to going to the theatre in the middle of a play, and having no idea what had happened before or after. She felt entirely conscious while she was seeing the visions. Moreover, she did not recognize any of the people or things that she was hallucinating.

“She was rather frightened, bewildered,” Sacks said. “She wondered in particular whether she was becoming demented, whether she had had a stroke, whether she had been given the wrong medications.”

After examining the patient, Sacks found no medication or sign that anything was amiss; she was mentally fit. However, when he found that she suffered from macular degeneration, a disease which progressively destroys the corneas, he concluded that she suffered from a rare condition called Charles Bonnet Syndrome, or complex visual hallucinations in the visually impaired.

“I said this is not uncommon in people who’ve lost their vision, this is the brain reacting to blindness, to loss of visual input,” Sacks said. “The visual parts of the brain have to be active all of the while, and if they’re not being employed by the eyes, or the imagination, then they will dig down into memory and cause hallucinations.”

Sacks said this is true of other senses as well, and noted that the brain begins to compensate when deprived of stimulation even for a short while.

“If one becomes deaf, one hears things, especially music. If one loses one’s sense of smell, you can have olfactory hallucinations,” he said. “…Even if one is blind-folded for only two days, the brain has to be active.”

Another very common form of hallucination is “hollow bereavement,” where a widow or widower after a long, happy marriage will see the face or hear the voice of the lost person.

“And this is not felt as spooky or threatening or unpleasant,” Sacks said. “It’s nearly always felt as comforting, and as natural, and as somehow helping to heal the abyss that has been left by a death, and maybe it’s part of the mourning process.”