For Dana Point author Gerald Derloshon, 62, stateside surfing’s historical timeline is split neatly between B.G. and A.G. In surf speak, that’s Before “Gidget” and After “Gidget.”

The senior director of public affairs at Pepperdine University—a surfer since he was 13 who still logs 100 to 150 hours annually—explains how the campy 1959 Sandra Dee film is credited with introducing surf culture to teenagers across the United States.

“Before ‘Gidget’ nobody cared what trunks surfers wore, what they did or didn’t do,” he says. “The movie did really well at the box office.” And the culture it created roughly 60 years ago endures, riding tandem with a multibillion-dollar industry of high-end surfboards and apparel.

But back in those B.G. days, Derloshon says, riding waves was limited to just a handful, lifeguards mainly, who were inspired by California’s first lifeguard and first surfer, George Freeth, imported from Hawaii in the early part of the last century to safeguard swimmers in Redondo Beach.

While Derloshon delights in recalling those early years, he says he was drawn more to the surf culture that emerged in the late ’50s and early ’60s, in places like Redondo Beach, Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach and Malibu.

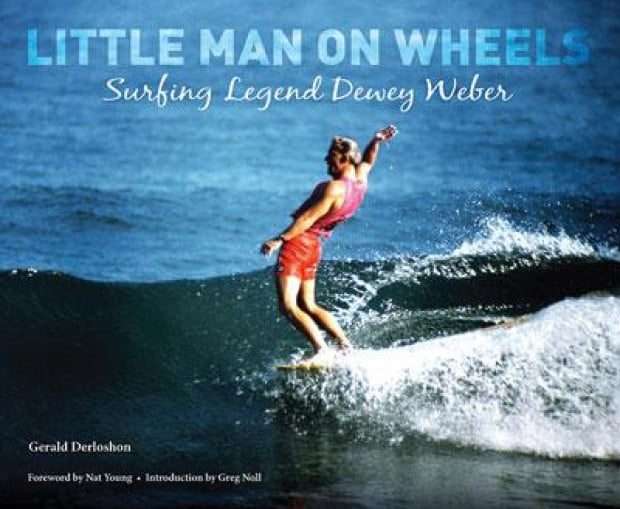

“These were key geographical places. It was all happening right there. Mira Costa High School (in Manhattan Beach) was the epicenter where in the 1960s people like Greg ‘Da Bull’ Noll and Dewey ‘The Little Man on Wheels’ Weber burst on the scene.” Colorful nicknames, Derloshon explains, are as common in surfing as sunburn. Weber’s nickname stemmed from his small, muscular frame and his fancy footwork.

Weber, who died in 1993 at 54, is the subject of Derloshon’s book, “Little Man on Wheels,” scheduled for release Sept. 20.

While he never met Weber, Derloshon says that as a surfer he was in awe of the Weber legend. As luck—or fate—would have it, a mutual friend introduced Derloshon to Weber’s widow, Caroline, the year Weber died.

The two hit it off, Derloshon says, and he was hired by Caroline to help her realign Weber’s surfboard company. “I worked on several PR and communications projects, and we developed a rapport from day one. She always said, ‘You have to write Dewey’s biography.’”

Four and a half years ago he finally began the project. Caroline provided the names of potential interviewees—Weber’s friends, colleagues and acquaintances. All told, Derloshon interviewed some 130 people—including Weber’s sons and daughter and his Cub Scout buddy/fellow surfer Noll—who shared their recollections.

“I was organizing the book in my head for years (it took him seven months to actually write the book), thinking how do you begin to tell a person’s life story?”

Although “Little Man on Wheels” follows Weber’s all-too-brief life chronologically (“from Dewey Weber’s charismatic ascent to the top of the burgeoning 1960s surf industry, to his free fall into alcoholism and financial ruin, ‘Little Man on Wheels’ tells of his enduring impact on the California lifestyle he popularized worldwide and how his legend and the global surf culture endures”), Derloshon says he did not want to end the biography on the sour note of Weber’s alcohol-related death. In the chapter titled “Family Matters,” a post-script of sorts, family members reminisce about Weber.

“Dewey is reborn through their memories. Lord knows Dewey Weber wasn’t perfect. He’d be the first to say he wasn’t. My hope is that I’ve portrayed his life accurately,” Derloshon says. “I’ve heard from several people who knew him well (and who read early drafts of the book) that that has been accomplished.”

Derloshon has presold roughly 120 hardcover copies of the “Little Man On Wheels,” which will be available through his website, www.littlemanonwheels.com, Amazon.com, Barnes & Nobel and locally at Diesel, A Bookstore, where he hopes to hold a book signing sometime this fall.

The Surfing Heritage Museum (www.surfingheritage.org) in San Clemente has scheduled a members’ reception and book signing from 6-9 p.m., Sept. 29, and Derloshon is moderating a panel on Weber that includes Linda Benson, five-time U.S. women’s champion; Steve Pezman, former Weber shaper and founder/publisher of “Surfers Journal;” Skip Frye, Weber team rider and prominent 1960s surfer; Caroline Weber, retired CEO of Dewey Weber Surfboards; and Shea Weber, Weber’s eldest son and current CEO of the 52-year-old San Clemente-based company.