Malibu is slowly bouncing back from the devastating 2018 Woolsey Fire.

City staff worked with Caltrans and Southern California Edison to upgrade and replace the batteries in traffic signals so Pacific Coast Highway will not be choked with traffic when the next disaster comes around. The city invested in bright red “beacon boxes” to clue firefighters called in from other cities to Malibu’s topography. And soon, residents will be able to hear a brand new emergency siren system, made possible by a FEMA grant, in the event of another wildfire or a tsunami, flood or terrorist attack.

Malibu residents are all too familiar with Southern California Edison’s intentional blackout program, called public safety power shutoffs (PSPS). The power company has already shut off electricity in parts of Malibu multiple times this year, citing Santa Ana winds and other dangerous fire conditions. Those shutoffs have sometimes extended to PCH, where many drivers are unsure what to do in the event of a traffic light outage.

“That’s a huge safety issue,” Malibu Public Works Director Rob Duboux told The Malibu Times. “People are supposed to [treat intersections as a four-way] stop when there’s no power, but some people drive through it and we’ve had several accidents.”

During the Woolsey Fire, a monumental PCH traffic jam became a major issue with the power signals out and residents scrambling to merge onto PCH from their neighborhoods in the canyons. If those signals had been on, they could have directed which cars had the right-of-way, speeding the flow of outbound traffic.

To remedy that, Duboux and his department coordinated with Caltrans and SCE to upgrade or replace all existing batteries in traffic signal controllers throughout Malibu. Now, when the power goes out, those batteries will be able to provide the signals power for a much longer time than before. The exact time length the batteries can hold out depends on the signal, but Duboux estimated all to be capable of lasting between four to eight hours. This is significantly better than the batteries the city had before, which Duboux guessed usually lasted between 20 to 30 minutes.

“This technology has been in place for awhile. We’ve been working with Caltrans and SCE since about the last PSPS,” said Duboux, who elaborated that the new batteries had taken approximately two to three months of work to get installed.

They were installed at no cost to the city; it is Caltrans’ responsibility to operate and maintain all traffic signals.

“The city is in here just trying to facilitate, to make sure Caltrans is doing their job and trying to make sure the community has continuous power to these signals when the power goes out,” Duboux explained.

As for SCE’s role, Duboux said the power company was considering more sustainable solutions, such as solar-powered batteries, though the main issue with solar was making sure the traffic signals still had power during nighttime.

Another Woolsey-driven update to the city is an emergency siren system, which will be useful during disasters where other types of communication—phones, computers and TVs—were not available, as occurred in 2018.

In early February, the city received a hazard mitigation grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to install sirens that would sound to alert Malibuites to wildfires and other disasters. That grant will cover 75 percent of the total costs—approximately $714,000. The rest—$238,000—needs to be matched by locals.

In a prepared statement, Malibu Mayor Mikke Pierson advocated for the project, which the city has been developing since 2019.

“[T]he Woolsey Fire … showed us the dangerous new normal of drought, climate change and California mega-fires,” the mayor said. “This siren system … could be a powerful step toward community-wide preparedness.”

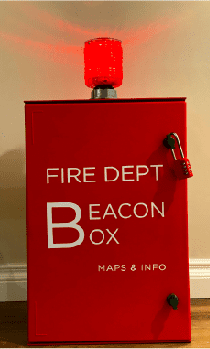

Malibu has also invested in “beacon boxes” for the next disaster, which are to be installed throughout neighborhoods and filled with helpful aids that firefighters from out of town might need.

At the most recent city council meeting, Pierson spoke of one fire truck that had arrived from San Diego to fight Woolsey. Its captain had chosen not to go up a canyon because it looked too dangerous from his vantage point, though Pierson insisted it was not. Multiple houses were lost that may have been saved from the flames.

“When fire departments show up from other cities or even other states, they simply don’t know where they’re going,” Pierson told The Malibu Times in a past interview about the boxes. “So being able to provide them information on a local neighborhood basis that can help them come in and make a difference and figure the fire is a huge upgrade.”

Each beacon box features a flashing red light on the outside and contains laminated maps and flash drives with digital versions of the maps, which will include vulnerable homes, fire hydrant locations, roads and driveways where it’s safe to turn around and other key information.

When the Malibu City Council reviewed the city’s budget at its last meeting, Public Safety Commissioner Doug Stewart spoke up, estimating that the boxes would cost the city $60,000.

So far, Pierson later told The Malibu Times, only one beacon box has been installed—the prototype. He said that the city had ordered “about 30” boxes from the company Flame Mapper, the same company that the city utilizes to provide prediction maps for all sorts of fire events.