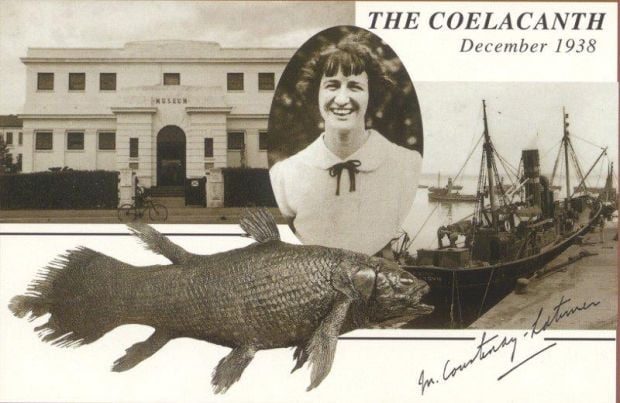

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, the first curator of the Natural History Museum in East London, South Africa, was presented a breathtaking, well-preserved coelacanth (pronounced SEAL-a-canth) by Captain Hendrik Goosen.

Coelacanths were presumed to have died off en masse like the dinosaurs during the last great extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period some 63 million years ago.

From the moment Professor JLB Smith, Rhodes University, South Africa, classified this rare living fossil Latimeria (after the East London curator) chalumanae (from the Chalumna River were it was thought to be found) a modern day mystery began to slowly unravel snippets of an ancient creature that seems to have trumped evolution.

In 1839, Louis Agassiz found the first fossil of a coelacanth in a Permian (290-240 million years ago) marl slate in Durham, northern England. He discovered that the fin rays supporting the tail were hollow and named it Coelacanthus (from the Greek for hollow spine) granulatus (after the tubercular ornamentation of its scales).

Other fossils around the globe depicted an extraordinary diversity of Devonian (410-360 million years ago) species that were as large as 10 feet and recent Cretaceous (138-63 million years ago) specimens were as small as one foot.

Prior to 410 million years ago, only a few spiky, low plants, along with some scorpions and other insects, lived on land. The continents were unrecognizable: large fresh water lakes and the oceans brimmed with life.

The diversity of aquatic life was dazzling, including: small, flat, heavily armored, bottom-feeding jawless bone-skinned fishes; giant nautilus, the size of a person; sea scorpions larger than lobsters; the first jawed fish; and primitive giant sharks – even then fearsome predators.

The fish of 400 million years ago were separated into two classes: ray finned with single dorsal fins and paired pectoral and pelvic fins common in modern fishes; and the lobed finned fishes – the coelacanth, the lungfish and the rhipidistian whose fins seemed to grow from the end of fleshy, limb-like lobes or toeless legs. Many were predators all were abundant.

About 360 million years ago, a fresh water lobed-finned fish sprouted legs, crawled out of the water and conquered the land. Since the time of Louis Agassiz and Charles Darwin scientists have been trying to discern which group: lungfish, rhipiditian or coelacanth, evolved legs.

Due to WW II, Professor Smith was forced to wait to get his next sample. He went to great lengths to distribute reward pamphlets all along the East African coast. Meanwhile Comoran fishermen had been occasionally catching coelacanths unaware of their scientific value. So it was only the next known to science that was caught in 1952 off the Comoro Islands, a remote volcanic archipelago at the head of the Mozambique Channel, halfway between Mozambique and Madagascar.

The anatomy of these primeval creatures is truly worthy of admiration and has allowed scientists a rare glimpse through the looking glass of 400 million years of time.

There are about 26,000 species of living fish and easily the coelacanth is the most mysterious.

The paired pectoral and pelvic fins appear similar to those of a lizard.

Coelacanths are able to swim forward, backward, upside down and on their

heads.

They have an extremely small brain (1/15,000 of an adults weight) with a unique intracranial joint, a feature previously known only from fossils. The coelacanth is able to increase its gape by a sudden opening of the entire head, giving it a powerful bite and compensating for its comparatively small, sharp teeth.

A rostal organ is jelly-filled with three exterior openings on either side of its snout – unknown in any other living creature. It acts as an electro-detector constantly searching for prey.

Coelacanths generally live below 1,300 feet, although they have been observed swimming as closes as 100 feet from the surface. During the day, they are inactive, seeking protection in volcanic caves. At night, these nocturnal predators are on the hunt. Their luminescent alien-green eyes have adapted to extremely low light levels.

Their spines are filled with a low viscosity lipid and the coelacanth is composed mainly of a flexible cartilage – similar to a shark. Its spinal fluid is viscous golden and rumored to act as an elixir. Coelacanths are thought to live for at least 40 years.

The coelacanth’s swim bladder is a slender fat-filled tube embedded in fat below the spine – it serves to increase its buoyancy. Buoyancy is maintained by the entire lipid-filled body of the fish and so, like many sharks, this ancient fish is capable of considerable vertical movement in the water column.

Coelacanths give birth to live pups, this predates the first mammals by at least 100 million years.

In 1987, a submersible located and filmed wild coelacanths off the Comoro Islands. Since then, coelacanths have been filmed or photographed in their habitat by divers and ROVs in Indonesia, Madagascar, South Africa and along the Tanzanian coast.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) listed the coelacanth in 1989 as severely endangered and strictly forbids any trade in this animal.

In 1998, Professor Mark Erdman, University of California Berkeley, discovered a new golden brown Indonesian coelacanth Latimeria menadoensis some 6,000 miles from the Comoro Islands in the Indian Ocean. In fact, the Indonesian coelacanth has the same coloration of the Indian Ocean ones: a clock spring steely blue with white to off white or pink blotches, the pattern of which is characteristic of the individual (rather like a fingerprint).

Other species of coelacanths are surely awaiting discovery; reiterating a heightened need for protecting all oceans, seas, lakes and rivers.