In 1974, the Mafia made Burt Ross an offer he couldn’t refuse.

He said no.

Ross not only lived to tell about it, but he aided in an investigation, as well as giving damning testimony in court, that led to the prosecution of seven New Jersey gangsters. All that, while being a first-term mayor of one of the most corrupt cities in America.

“Life twists and turns in ways you just can’t predict,” Ross said, speaking at a special event at Pepperdine University Wednesday. Speaking publicly about the incident for the first time in 10 years, Ross also discussed “The Bribe,” the book his brother, Philip, wrote in 1976 about the case.

In 1971, Ross was a Harvard-educated stockbroker with a law degree from New York University. But he was restless. At a fund-raising event, Ross said he was approached to run for mayor of Fort Lee, N.J., not far from his hometown of Teaneck.

“This was no plum job,” he said. “I was to be a sacrificial lamb. Democrats don’t win in Fort Lee. End of story.”

But with a young, dedicated campaign team, which included his brother, he shocked the political establishment and won in a landslide, even though Republicans outnumbered Democrats two-to-one. At 28, he was the youngest mayor in the United States.

Fort Lee, just across the George Washington Bridge from Manhattan, was known for two things: It was one of the most densely populated cities in America and, “It was a favorite place for gangsters to live and play,” Ross said.

“I wanted something to get rid of the boredom,” he added. “And being mayor is anything but boring. I learned quickly that it’s one thing to run for office, it’s another to serve.”

Replacing the old political machine with young, idealistic staffers, Ross’ administration quickly passed landmark rent-regulation legislation. Ross also rooted out the corruption around him— exposing the city tax collector as a tax evader and ousting the police chief, who shamelessly cavorted with known underworld figures.

But those accomplishments would become secondary once a developer named Arthur Sutton proposed a massive, three-million-square-foot, $250 million regional shopping center in the heart of Fort Lee. Ross was against it.

One fateful night in May 1974 came a knock on Ross’ front door. Standing before him was a man who called himself “Joey D.”

“He was straight out of central casting,” said Ross, “right down to his pinkie ring.”

Joey D. wanted a vote delayed on necessary variances by the board of adjustment the following day. Ross said there was nothing he could do. First, Joey D. offered Ross $100,000 to delay the vote, but when Ross balked, he upped it to $500,000. Ross refused. Not even the gun in the gangster’s belt could change his mind.

What Ross did do was contact law enforcement. The district attorney’s office was skeptical. This was the era of Watergate and rampant political corruption on all levels. “They never had anyone come forward like that,” Ross recalled. “They weren’t prepared.

“I was caught between a rock and a hard place, between a desperate mobster and a disbelieving district attorney.”

But after another visit from an even more threatening Joey D.—Joey Diaco, a well-known crime figure—the FBI entered the picture and made Ross an offer of their own. It was one he had been urging himself from the beginning: Tape their conversations.

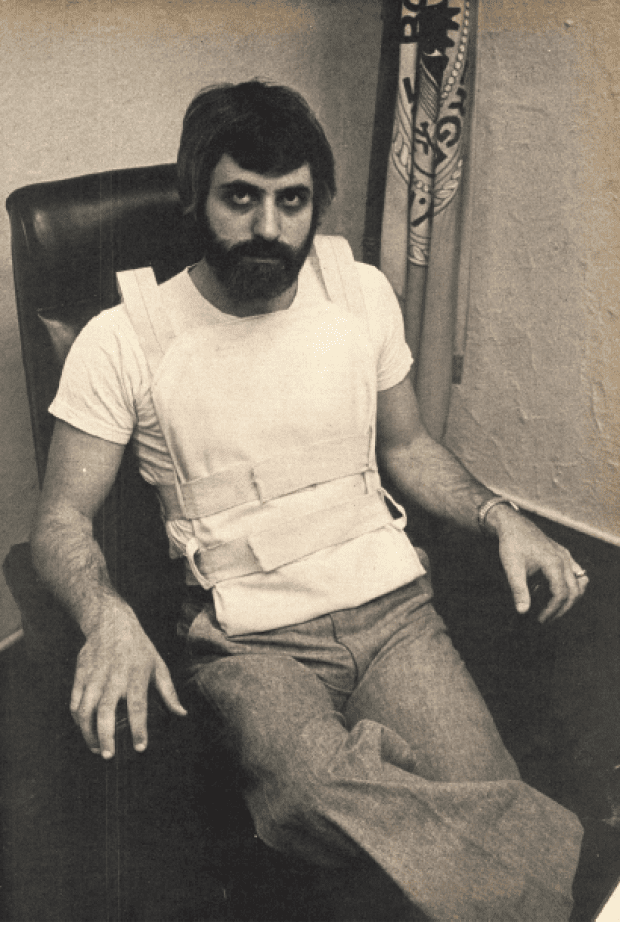

Wearing a listening device in his belt, and watched by undercover FBI agents, Ross met with Sutton and Diaco at a restaurant. The wire got it all.

Still, it took another 13 days and another nerve-wracking meeting before the FBI made arrests, seven in all. Little did Ross know, that was just the beginning.

The mayor of Fort Lee was forced to go into hiding as the FBI put together its case and he was able to testify in court and end the ordeal. Even after his return to his mayoral duties, Ross had around-the-clock protection and even wore a bullet-proof vest.

“Actually, the scariest thing was the protection,” he said of his gun-toting bodyguards.

In the end, the seven were convicted and sentenced to five years in prison, although a later judge reduced the sentences to six months.

Ross, who moved to Malibu a year ago with his wife, Joan, in order to be closer to their children, left politics after his one term of office was completed, although he did have an unsuccessful run at a congressional primary in 1980.

But after all these years, the 69-year-old Ross doesn’t flinch when asked if he’d do anything differently, like maybe taking the money.

“I think I did it instinctively,” he said of his refusal. “I didn’t like being told what to do.”