‘300’: Those manly Spartans

What’s an historian to make of the new film “300?” It’s based on a graphic novel after all, a genre more suited to superheroes than Spartans. It also boasts a set of fantastical creatures-ogres, trolls and the like-that seem to have wandered in from a “Lord of the Rings” movie. And the stylistic violence is, frankly, over the top. Lots of limb severing and decapitations, in super slow motion no less.

Yet there’s a real history here, buried inside the mythic trappings. Three hundred Spartans did make a stand at Thermopylae in 480 B.C., and in that narrow pass held off for days a massive Persian army threatening to conquer Greece. And, as the film shows, Sparta’s example did inspire Athens and the other Greek city-states to rally and drive off the Persian invaders.

But if the fantasy elements in “300” throw you, here’s a guide to tease out the history from the myth.

Q. These Spartans drip with testosterone. Were they that tough?

A. They were all that and more. The Spartans built their entire civilization around the military and expected every citizen to be stoic-never to cry out in pain, never to complain, never to surrender.

But it was a harsh culture. Sickly babies were discarded, thrown off a cliff outside the city. Children were kept hungry to promote self-sufficiency. And signs of mercy indicated weakness.

But-and here’s what the film overlooks-Sparta’s powerful army was not primarily designed to combat outside enemies. It was the enemy within-the massive number of slaves kept in Sparta, threatening constantly to revolt-that most concerned the Spartan military. Those slaves, ironically, made possible the Spartan culture (and that of Athens as well). Slaves worked as the butchers, bakers and candlestick makers, allowing free Greeks to follow their bliss, whether it was military training, art or philosophizing.

Q. Slaves? I thought the Greeks were fighting for freedom, and only the Persians kept slaves.

A. The film certainly gives that impression. The Spartans, we’re told, are manly men who represent freedom, liberty and justice for all, while the Persians are decadent slave-drivers, who can’t fight worth a lick and come off as rather effeminate.

The truth is a lot more complicated. The widespread use of slaves shows that the Greek concept of freedom was limited to a select group. And when the Spartan army wasn’t bravely battling Persians, they were often threatening their Greek neighbors. The Persians, on the other hand, far from being sissies, were fierce warriors who had conquered Asia Minor. And they were acknowledged by most to be fairly merciful overlords of the regions they ruled.

Yet a deeper truth lurks behind the film’s simplistic message. Greek city-states like Athens were the first in the world to experiment with that radical new form of government called democracy. Had the Persians conquered them, those ideas, and much of Greek culture, might have gotten snuffed out before it reached its full flowering.

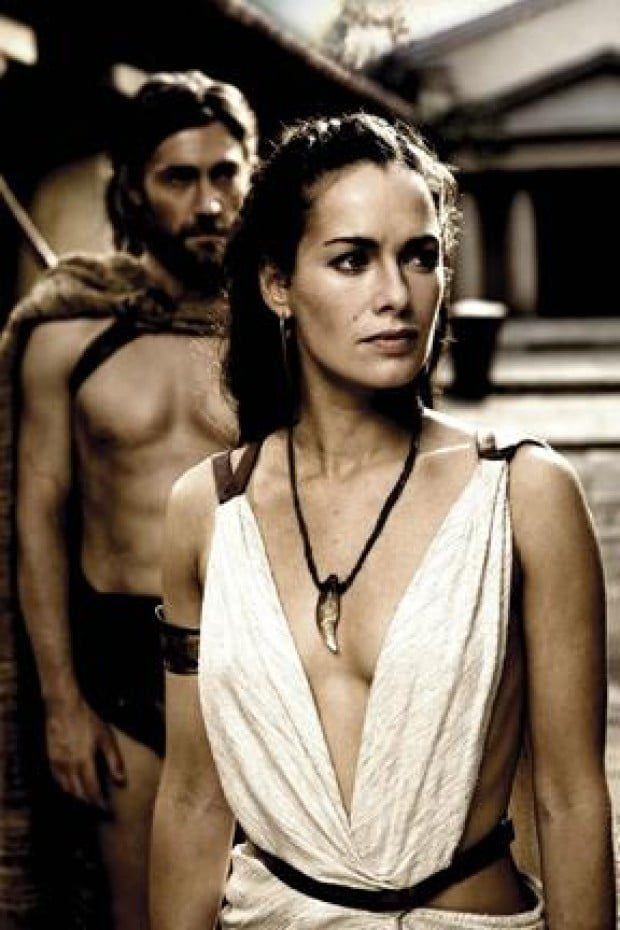

Q. Leonidas, the Spartan king, has a wife as tough as he is. Did they exaggerate that?

A. Not really. Spartan girls were bred to be almost as tough and strong as the boys, since it was up to them to produce future warriors. And Spartan women had the time to engage in physical fitness, since all the traditional women’s work-cleaning, cooking, even caring for children-was conveniently being done by slaves.

In the film, Leonidas’s wife sends him off to Thermopylae with the bracing command, “Come back with your shield, or on it.” We don’t know if she actually said that to him, but it was the traditional line Spartan mothers gave to their sons as they marched off to fight.

Q Any other lines that are historically accurate?

A. There’s a great one that’s straight from Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian. As the massive Persian army advances toward Thermopylae, the outnumbered Spartans are told that the Persian arrows will “darken the sun.”

“Good,” one Spartan replies. “Then we will fight in the shade.”

Best line ever. The filmmakers thought so too, since they used it twice.

Q. The Spartan helmets look cool, but did they really go to war wearing helmets and little else?

A. No, like most sensible solders, they wore breast shields, leg and arm braces, and all kinds of stuff designed to keep them from getting injured on the battlefield. I think the filmmakers decided that seeing the actors’ rippling six-packs would reinforce their manliness.

And speaking of the Spartans’ masculinity, Herodotus provides an amusing detail. Before the battle, Persian scouts were puzzled to see the Spartans taking the time to “comb out their long hair.” It was a typical Spartan battle preparation, but the film left it out.

Q. What’s a good source for more on Thermopylae?

A. Try “The History of Herodotus.” Though written 2,500 years ago, it’s still a great read.

And I think Herodotus would have liked “300.” His story teems with the same blood and guts, glory and horror shown in this film, and he, too, wasn’t above twisting some details to spin a better yarn. Probably, like most of the film’s intended audience, he’d brush off my snarky comments and enjoy the film.

Cathy Schultz, Ph.D., is a history professor at the University of St. Francis in Illinois. You can reach her through her Web site at www.stfrancis.edu/historyinthemovies