Tiles saved the Adamson House, theorized Cristi Walden, one of the board members of the Malibu Lagoon Museum.

In the 1970s, she explained, the state wanted to tear down the building and turn the land into a beach parking lot. But, because the house was brimming with vintage tiles, there was a change of heart and the Adamson House was preserved as a historical landmark.

“There’s not a lot of history in Malibu,” said Walden, “and the Adamson House is probably the only real historic landmark. Had it not been protected, moreover, the appreciation for tiles might not have taken place.”

Walden is also one of the curators for the California Tile Exhibit at the California Heritage Museum in Santa Monica.

The show, which will run until the end of September, features more than 1,200 individual tiles, 50 tile tables and 50 murals, all meticulously installed by the museum’s small staff. According to Tobi Smith, the museum’s director, it took four people to hang the show’s largest murals, which are 91-inches high, on the specially built second floor gallery wall.

The ceramic artworks, which were borrowed from 60 collectors around the country, represent about 34 northern and southern California tile factories, including many samples from May K. Rindge’s Malibu Potteries.

“This is the real deal,” marveled Janine Waldbaum, owner of Malibu Tile Works, on opening night. “These are the authentic tiles from the 1920s, the Golden Era of tile making.”

Architects during California’s ’20s building boom were enamored with Spanish and Mediterranean building styles as the rest of the population hungered for handmade arts and crafts in the face of dehumanizing industrialization. The demand for ceramic tiles was strong and the trend did not escape May K. Rindge, widow of Frederick Hastings Rindge, the last owner of the Spanish land grant that later became Malibu.

Rindge, a capable businesswoman trying to recover money lost in legal fees to halt construction of a highway through her estate (today’s PCH), recognized that there was a muddy gold mine of red and buff burning clay existing under her feet. Also working in her favor was an abundant supply of water and a convenient transportation system that could carry craftsmen in from Santa Monica and facilitate the distribution of finished products to buyers.

In 1926, she commissioned Rufus B. Keeler, an expert ceramist who had worked with and started some of California’s most successful tile companies (also represented in the Heritage Museum exhibit), to construct and operate Malibu Potteries. The artist had spent years researching Spanish and Moorish decorative tiles and aimed to replicate the exquisite style and vivid colors in his own work.

The result: strong, durable tiles decorated with brilliant glazes renowned for their color and clarity.

“The newer tiles are still hand-glazed and it’s still a very labor-intensive process,” said Walden. “But while they are beautiful in their own right, they’re just not the same [as the vintage tiles].”

One of the reasons: the older artisans used dangerous chemicals not available today like uranium, which was used to produce a unique orange color, and other compounds with high lead content.

Only the vintage tiles, furthermore, offer a glimpse into California’s historic fascination with exotic and local themes.

The “Saracen” style, for example, coined by Keeler, celebrated the spread of Islam into Spain and France in the Middle Ages. Since Muslims were forbidden to represent images of living beings in their art, these tiles are predominantly abstract and geometric.

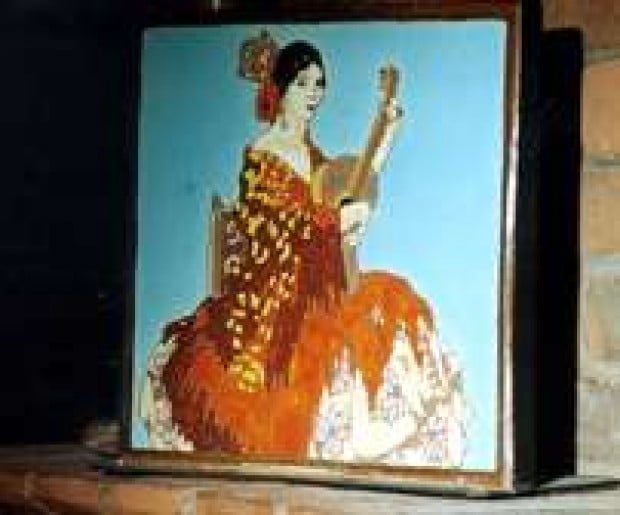

The glorification of things Spanish is seen repeatedly in the Heritage Museum show through scenes of dancing senoritas and dons.

Tiles with Mayan and Egyptian designs followed the fascination over archeological discoveries of pyramids in Egypt and Central America, and Mexican caballeros in sombreros taking siestas recalled California’s Mexican heritage.

“These historic tiles are getting harder and harder to find,” Walden worried. “Every day in Los Angeles, bathrooms are being remodeled and houses that were decorated with these wonderful tiles are being torn down. I’m hoping people will begin to realize that the tiles are special and that they are worth saving.”

The California Heritage Museum, located at 2612 Main Street, Santa Monica, is open Wednesday through Sunday at 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. The exhibit, “California Tiles: The Golden Era 1910-1940,” will continue through September.