Bad news for public safety fire risk in Malibu, good news for cold camping enthusiasts: The California Coastal Commission voted on July 7 to allow the LA County Local Coastal Program (LCP) for the Santa Monica Mountains to include cold, low-impact camping in ESHA (environmentally sensitive habitat areas) as one of its allowable activities. Not only that, but commission staff actually loosened some of LA County’s proposed rules for cold camping—rules that were carefully crafted to take into account the concerns of Malibu residents and the county in 2019.

The definition of “low-impact camping” is an area designated for “carry-in, carry-out” tent camping accessed by foot or wheelchair. “Cold camping” means no open flames.

Coastal commission staff did not approve of the wording of rules in the county LCP that were influenced by Malibu, so they “coordinated together” with LA County to revise them—without consulting Malibu. No one from LA County appeared at the coastal commission virtual meeting on July 7 to speak on the county’s behalf or express support for the revised LCP, although the commission did receive a letter of support from County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl.

California State Senator Henry Stern, who represents Malibu and the Santa Monica Mountains, sent a letter to Kuehl and also called Coastal Commissioner Dayna Bochco on July 5 with his concerns about “the lack of campsite inspections during red flag days,” according to Bochco. Malibu City Council Member Karen Farrer urged every member of the commission to read Stern’s letter.

On July 7, despite heartfelt comments from 10 public speakers appearing on very short notice, including Malibu city officials and scientists—many emphasizing that some campers ignore rules and light fires anyway—the commission voted down the county LCP and passed their revised version of it.

“To say we’re nervous is an understatement,” Council Member Mikke Pierson told the commission. “We’ve already had numerous fires this year from people camping.”

“There’s no such thing as a no-impact campground in Malibu,” commented Malibu resident Wade Major. “It’s a constant war zone … and there are insufficient staff patrols for any of these mountains.”

“Our coastal zone is a tinderbox with the drought and much of the prime habitat invaded by weeds,” said Kim Lamorie, president of the Las Virgenes Homeowners Federation. “Camping imposes a risk that can be mitigated.”

Among the highly controversial changes the coastal commission made to the proposed LCP was shrinking a required 100-foot buffer between campsites and the top banks of streams or riparian vegetation areas to only 50 feet. Scientist Emily Parker from Heal the Bay stated the environmental nonprofit told coastal staff previously that a 50-foot buffer wasn’t enough to protect streams from erosion.

In addition, no specific standards or descriptions of “fireproof cooking stations” to be installed at the campgrounds were included.

The original LCP wording specifically prohibiting camping during red flag days was changed to say, “Camping is prohibited when hazardous conditions exist (e.g. when during ‘red-flag” wildfire warnings or flash flood warnings are issued).”

Some say “red flag days” needs to be spelled out, not just lumped together with “hazardous conditions.” In response to questions, Kuehl’s office wrote TMT that “The proposal does not eliminate red flag days; it broadens the definition [to include other] hazardous conditions.”

Perhaps the most controversial LCP change made by the commission was removing a proposed requirement for rangers to personally check all low-impact campsites daily. The reworded rule says only, “Campgrounds will be periodically patrolled to enforce the policy.”

City of Malibu Principal Planner Adrian Fernandez criticized the fact that “the provision of campground staff for daily inspections was removed and should be reinstated as opposed to ‘periodic patrolling.’”

“It’s ridiculous to tell MRCA they have no need to police their own campsites,” Mayor Paul Grisanti told the commission.

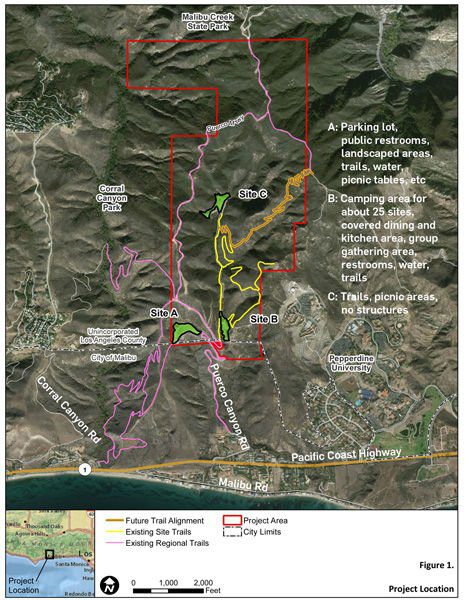

It’s assumed that the MRCA—Mountains Recreation Conservation Authority, headed up by Joseph Edmiston—is behind the push to get low-impact camping into the LCP, since they have several parks in the LCP area—including Ramirez and areas of Puerco, Corral and Tuna canyons.

When Bochco asked coastal staff why it “was proposing laxer enforcement than LA County,” Steve Hudson, district director, South Central & South Coast LA County, responded, “So MRCA could operate such a facility more easily, especially in areas with remote access.”

The campgrounds could be a long time coming. Hudson also emphasized that “There is no shovel-ready project for low-impact camping at this time, and any actual project would have to go back through the county for approval.”

Hudson explained that the LCP would now require a Coastal Development Permit (CDP) for each campground and a specific “management plan” for each one that would provide “project level detail” such as how often it should be inspected and what kind, if any, fireproof cooking station would be installed there.

The decision was decried in Malibu, with city council members complaining during their Monday, July 12, meeting that coastal commission staff did not appear interested in locals’ concerns.

“They gutted two of the most important rules,” resident Barry Haldeman said in a phone interview following the decision. “If you don’t have supervision, you run the risk of having people that don’t follow the rules or realize the dangers. Has the board of supervisors or coastal commission even talked to the fire department about this to see whether they could defend low-impact campsites?”

The bottom line, according to Haldeman, was that “No one wants to prevent access to the Santa Monica Mountains, but to create these particular circumstances is crazy. We have a responsibility to manage our precious resources and this falls short.”

When Kuehl’s office was asked whether she supports the coastal commission’s changes, they responded she does not “intend to oppose the coastal commission proposal.” Her office clarified that the process going forward will include, “A public hearing at the board [of supervisors] in a couple of months. Assuming it’s approved, it would go back to the coastal commission for certification, and then be forwarded to the attorney general.”