In a video message to the Malibu community on Nov. 9—the two-year anniversary of the Woolsey Fire tearing its way through the heart of Malibu—Mayor Mikke Pierson urged Malibuites to prepare for future fires, adding “we do look back, while we look forward.”

That sentiment guides The Malibu Times’ multipart series marking the second anniversary of the fire, the most devastating disaster to occur in Malibu in written history.

In the time since, 16 homes within Malibu city limits have been rebuilt with hundreds more in the pipeline. But rebuilds only tell a small fraction of the story.

This week, we recall the events of the fire and discuss what has changed in the two years since: safety improvements, new rules and standards, budding relationships, and more. Next week: where the home rebuild stands and how the city’s efforts compare to those in “county Malibu” outside city limits. Later in the month: recovery and struggles in the Santa Monica Mountains.

Painful lessons

Malibu City Council decided on Monday to move forward with a citywide siren warning system for wildfire evacuations and tsunamis, the latest in an ongoing series of public safety improvements that have come through in the years since Woolsey.

“I just want to remind everybody on the council, here we are on the anniversary—the second anniversary of the Woolsey Fire,” Council Member Karen Farrer said. “Public safety is our No. 1 priority, we voted, on the two years [Mayor] Mikke [Pierson] and I have been on council. I’d like to see this happen as soon as possible.”

All five members of council voted to move forward with the siren plan (including discussing with area cities and LA County). The design and environmental reports are projected to cost the city $237,908 (just a quarter of the total fee, thanks to a FEMA grant), and could cost nearly $2.5 million to construct if the city opts for the most expansive plan of 36 sirens, all with steel poles and cement foundations.

Earlier in the evening, Pierson rattled off a laundry list of other improvements that have been made in the city to help avoid a second Woolsey situation. They included a system of information stations (part of the city’s “zero-power plan”) that will spring up at gathering places around town to showcase the latest news on sandwich boards and a network of radio receivers installed with the help of CERT, the community emergency resource team.

KBUU-99.1, which is prepared to issue emergency round-the-clock broadcasts in the event of a fire, has moved to solar panels to help maintain electricity in the event of an outage.

A fire safety landscaping ordinance now exists to prohibit some of the most dangerous types of landscaping, the kind that can blow burning embers under a roof or catch fire while attached to a home or other structure. Adopted in March 2019, the ordinance mandates a five-foot defensible space buffer exterior walls, meaning no landscaping can come up to the edge of your home. Palm trees are prohibited, all tree heights are limited and highly flammable trees may not be planted within 50 feet of any structure. Flammable landscaping material such as shredded bark and artificial turf are prohibited within five feet of a structure. Wood chips and shredded rubber are prohibited anywhere on site.

The city now has a system of evacuation zones and is trying to get emergency survival guides into the hands of all interested residents (the survival guide can be found entirely online by visiting malibucity.org/survivalguide).

Evacuation zones are numbered 11–14, with Zone 11 stretching from Sunset Boulevard to the Malibu Pier, Zone 12 stretching from the Malibu Pier to Latigo Canyon Road, Zone 13 running from Latigo Canyon Road to Busch Drive and Zone 14 running from Busch Drive to Ventura County Line.

When it comes to placing blame for mishandling the fire and its aftermath, fingers point in all directions: Was it a failure by joint command and CalFire? Failure by city staff and elected officials? A failure of the sheriff’s department and California Highway Patrol? Failures of individual homeowners to fire-harden their homes? Failures of firefighters to make real efforts to save structures?

Local and county officials endured a torrent of anger and frustration from residents who saw firefighters in parked engines watch the fire burn down the hill in Malibu Park or into the neighborhoods of Point Dume and apparently sit idly by. In LA County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl’s after-action report, firefighters described the danger of out-of-town personnel taking their fire equipment into unknown neighborhoods where they could get stuck in a dead end, a box canyon or have no access to water. Now, the city is considering a project to ensure firefighters can access information they need for each Malibu neighborhood, beginning with a prototype in Malibu West.

“The problem with these large, mega-fires is that it requires mutual aid from other fire departments to help out because they’re bigger than our local fire department can handle,” Pierson told The Malibu Times on Tuesday. “When fire departments show up from other cities or even other states, they simply don’t know where they’re going. So being able to provide them information on a local neighborhood basis that can help them come in and make a difference and figure the fire is a huge upgrade.”

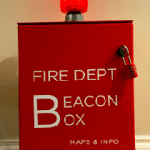

The prototype “beacon box” will feature a flashing red light to direct firefighters. Inside are laminated maps and flash drives with digital versions of the maps, which will include vulnerable homes, fire hydrant locations, roads and driveways where it’s safe to turn around and other key information—so that “firemen can quickly see where they need to go,” Pierson said.

“During the Woolsey Fire, the first fire engine I saw in my neighborhood was from San Diego, I believe,” Pierson recalled. “I was trying to save a house and ran down the street and tried to get them to help, but he was afraid to get stuck.” Despite Pierson’s best efforts, the fire engine would not turn down the street.

“I wasn’t sure whether he had other orders, but I get it—they’re not supposed to put themselves in a situation where they can be hurt,” Pierson said.

With “beacon boxes,” firefighters will know which routes are safe to turn down and will not be forced to avoid a neighborhood for fear of unknown danger.