As a 59-year-old quadriplegic with plenty of health issues, Gary Horn would like to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Last week when a friend erroneously told him he was eligible to be inoculated, Horn secured an appointment online. Unfortunately, after an hour drive to California State University-Northridge, an attendant unceremoniously turned him away.

“She was very clipped with how she dealt with me,” the 32-year Malibu resident recalled of his unpleasant experience.

Under current California guidelines, only healthcare workers (tier IA) or those over 65 (tier IB) are eligible for vaccines (as well as nursing home residents). That leaves most of those under 65 with chronic medical conditions out of luck, and it frustrates those at higher risk from COVID-19 complications should they contract the deadly disease when they see privileged or lucky “vaccine chasers” get a shot, many of whom have the privilege to wait it out in parking lots for hours on end or rush across town at the drop of a hat to jump on a spare dose.

It’s a problem, too, for the Founding Director of JLA Trust & Services, a nonprofit that advocates for those with a wide range of disabilities and special needs, including Michelle Wolf.

“We have a 26-year-old son with multiple disabilities who can’t wear a mask due to his sensory challenges,” Wolf described. “It is ridiculous that I have been vaccinated as my son’s in-home health care worker, yet my son may have to wait until April or May to get his shot.”

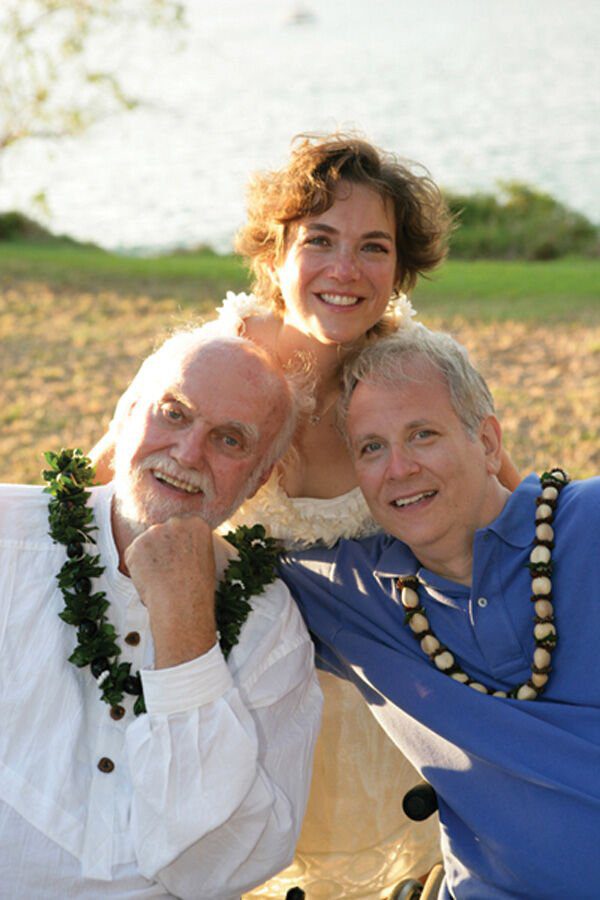

Horn, who suffered a spinal cord injury at age 19, stressed that he is not unduly leveraging his condition.

“I have never played the wheelchair card … If anything, I bend over backwards not to do that,” he said. But the screenwriter and Huffington Post columnist described his frustration.

“Fifteen percent of my body is normally neurologically enervated,” he said. “Doing simple math comparison suggests my lung capacity is 70 percent impacted because of lack of neurological input.” Horn has to use a respiration device to sleep. “I’m obviously tremendously susceptible to any respiratory virus. The reality that I live with is that, though I am 59, if you looked at an actuarial table I have lived far longer than my expiration date because people with C5-6 spinal cord injuries do not live for 40 years. Consequently, I am severely compromised.

“I want to underscore that I am not seeking sympathy,” he said. Consequences of Horn contracting the disease would likely be dire.

Horn went on to clarify his empathy for other high-risk groups that are often underserved.

“The rollout of this vaccine has been catastrophic for a lot of people, most principally the African American and Latinx communities,” Horn continued. He disparaged vaccine chasers—many from the west side—who have been getting inoculated at a South Los Angeles clinic before the clinic’s neighboring residents “at the expense of people who are unable, for language barriers, lack of WiFi or inability to navigate the maze-like rubric, to receive a shot apportioned to that community which is rife with COVID. It’s beyond inequity. This is maddening to me.” Meanwhile, distribution across Los Angeles has been slowed by shortages, with officials announcing this week, from Feb. 8-12, only second doses would be going out due to supply issues, meaning tens of thousands of eligible candidates will be forced to push back their appointments.

California’s age-based vaccine rollout follows most other states’ policy. Only a handful of others, including Kentucky and Montana, now vaccinate anyone over 16 with a high-risk medical condition.

Horn has been trying to get the ear of government officials.

“I’ve been in a phone queue for an exhaustive amount of time,” he said. “You’d have an easier time reaching Justin Timberlake or Tom Brady. They [politicians] are not interested in hearing from constituents.”

Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s health and human services secretary, indicated last week a change in rollout could be implemented.

“We are leading our vaccination effort by focusing on protecting those who have the highest risk and those who may suffer the worst consequences from COVID,” Ghaly said, adding that the state is “working with the disability community, working with those who take care of individuals with serious chronic conditions, beginning to galvanize around a policy that we will announce later.”

Horn hopes policy will change for those most at risk.

“I have a very blessed life,” he said. “But this is a particularly egregious circumstance.”