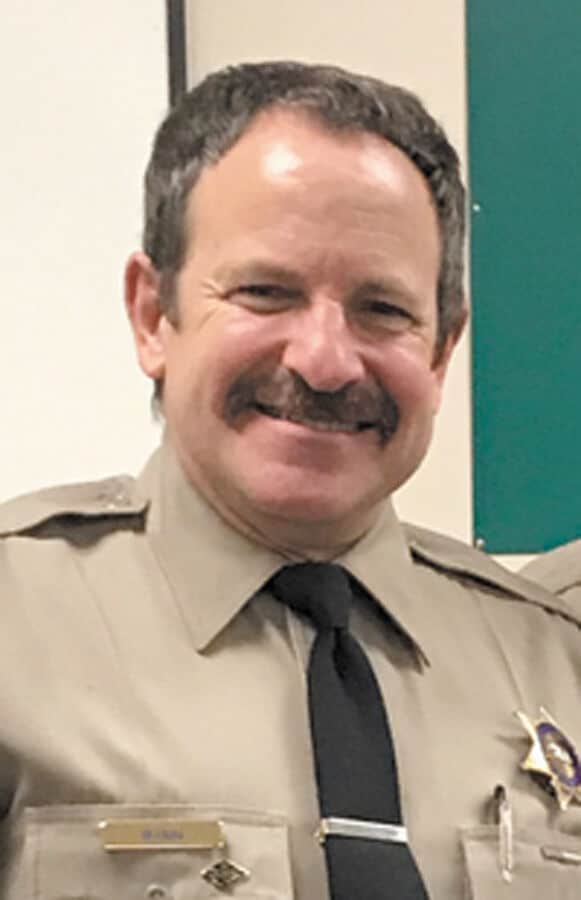

LA County Sheriff’s Deputy Mark Winn quietly retired in July after 33 years of service—including 27 years at the Malibu/Lost Hills Station. During his time in Malibu, he’s seen it all as a first responder: fatal accidents, the Woolsey Fire and the Old Topanga Fire of 1993. Winn has worked tirelessly with the local homeless population with fellow deputy Mike Treinen, and also done everything from beach patrol to handing out speeding tickets to animal rescues.

Winn, who began his tenure at the LASD in East LA, noted the stark differences between Malibu and that neighborhood back when he first came to Lost Hills.

“My first two years included the 1993 Old Topanga Fire and, just a few months after that, the 1994 Northridge earthquake—that was my welcome to Lost Hills,” Winn said.

“East LA doesn’t have hills and fires, and there’s a whole different set of issues here as far as law enforcement. There, it’s all about crime and violence. In Malibu, it’s about traffic and community policing—a much different culture. This area is also huge—we have a 187-square-mile patrol area versus two square miles in East LA. It can take 30 to 40 minutes to answer a call here.”

“When the ‘93 fire broke out, I was sent to the old Malibu station to run the command post, and this was in the days before cell phones and with old computer systems. We had 900 pieces of fire equipment come here and hundreds of law enforcement officers from all over, which we sent up the canyons to evacuate people. I learned all the ins and outs of the Santa Monica Mountains and its miles and miles of roads. It was my baptism by fire,” he said.

“Then the Northridge earthquake damaged a lot of homes at higher elevations in the mountains—it knocked some houses right off their foundations. We had to patrol those areas and put out spot fires,” he continued.

Some residents first became familiar with Winn when a local paper ran a photo of him walking a sea lion on a leash across PCH. The sea lion had managed to cross PCH at La Costa Beach, then took a rest and was starting to cross back over again toward the ocean. “He started to get out into traffic, and so a surfer gave me his surfboard leash to put on him, and my two partners stopped traffic on PCH, and we got him across and out to the ocean,” Winn explained.

That wasn’t his only exotic animal rescue—he also rescued a capuchin monkey from inside a car.

Winn was also known in Malibu for giving out candy.

“I started passing it out to people on traffic stops, then I began putting it in their mailboxes, and then it became a Christmas thing,” he said. “I’d go through about 1,200 candy canes, leaving them in envelopes in people’s mailboxes that were on my ‘good’ list.”

Even after the Woolsey Fire, if he went to an address and the house had burned down, he would still leave the candy in the mailbox—if there was one.

“One of the hardest things is thinking about what these people have gone through,” he said.

Winn has helped out with Toys for Tots, worked at pancake breakfasts at the station and even dressed up like an elf at Christmas.

“I also worked under Lt. Jim Royal to get the Volunteers on Patrol (VOP) program going in Malibu. We already had it on the Valley side, and when Malibu VOP started to pick up, I jumped into that,” he said. “I saw the potential of using people in the city to be our eyes and ears and help us with traffic control. They would go out in the cars and report things they saw to us, helping their community. For us to have three more cars out there calling information into the station, and also doing traffic control, really helps.

“I was also the Sheriff Department manager for CERT teams, and for the last five years, I managed the Topanga CERT team,” he said. “After retirement, I stayed on as a member.”

He also shared an anecdote about speedsters in Malibu—it turns out some of them may look pretty familiar.

“Many people have written letters to the captain and the city about speeding and reckless driving,” he said. “But ironically, I’d say 70 to 80 percent of the speeding tickets I’ve given were to Malibu area residents, who would scold me for not doing something more important, like solving crimes. I’d have to tell them, ‘I’m here writing tickets because your neighbors are complaining about speeders.’ Most of the speeders are not outsiders.”

In his first six months of retirement, Winn has not been resting—he’s still passionate about training people on emergency procedures.

“I’m not one to sit around the house,” he said. “I’ve been putting together classes for CERT and VOP, getting communications radios brought up to date with new frequencies, and training the LAPD on the Topanga zones, the Malibu dolphin stickers program and other evacuation protocols.” He is also working with hospitals on evacuation procedures.

“I don’t want to lose the momentum of people being prepared for emergencies. Even if you get COVID and have to go quarantine, you still need to have a go-bag ready, and you’ll still be displaced for 14 days,” he cautioned.

“I was very happy here and I’ve met a tremendous number of fantastic people … Some of the people were born and raised here and have been out in the mountains for 60 or 70 years,” he said. “You meet everyone here from the ultra-rich to the third-generation residents whose parents bought houses in the 1950s.”

Over the years, Winn said, the Lost Hills Station had become his home.

“A lot of deputies have come and gone from Lost Hills over the years, but there was a small core of us who decided we wanted to make this station our home,” Winn said, adding, “I love the area—I wouldn’t have traded it for anything. I got offers for transfers, but I didn’t want to leave my people.”