They are our family, friends and neighbors. In Malibu we see them hanging out on restaurant patios, in grocery stores and playing at the beach. We get used to their presence. Then, one day, as with all beings, they are gone. Decisions must now be made.

Nestled among the rolling hills of what is today Calabasas is the historic Los Angeles Pet Memorial Park and Crematorium. Just the second pet cemetery in the country when it opened in 1929—the first was the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, dedicated in 1896 in Westchester County, New York—animal lovers of all kinds have been coming here to lay their beloved pets to rest for more than eight decades.

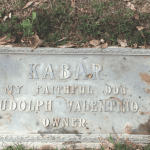

A walk through the park shows how dedicated people have been to their pets even years later. Out-of-towners make pilgrimages to visit; fresh flowers, dog toys and gravestones with pictures of pets literally cover the grounds.

After giving up a corporate job, Emad Whitney began as a groundskeeper for five years before becoming the park’s manager. It’s a position he holds with a great sense of obligation.

“(I think) this job requires a certain kind of person,” Whitney said. “I’m a pet lover myself and (I feel) this is a great service to those who have lost a pet. It gives me extreme pride to make it easier for the owners to get through the process.”

The cemetery lies among grazing ranges once owned by Hollywood financier Gilbert H. Beesemeyer. Before being sentenced to 40 years in San Quentin for embezzling eight million dollars in 1929, he had subdivided his property into 10-acre parcels. One of these parcels was purchased by Dr. Eugene Jones, who ran one of the first small animal hospitals in Santa Monica, the E.C. Jones Veterinary Hospital on Santa Monica Blvd. in 1928. After burying his own dog on the property, he opened the L.A. Pet Park and a Hollywood pet funeral parlor to help his clients deal with their feelings of bereavement. The L.A. Pet Park became the second pet cemetery in the United States.

The L.A. Pet Cemetery officially opened on September 4, 1928, with a mortuary, crematory and brick mausoleum added in 1929. At that time, coffins cost $7.50 and cremation $17.50, costly items during the Great Depression. True animal lovers spare no expense for their pets’ comfort and safety, even in death. During the 1930s, pet funerals caught on with the “Hollywood set.”

Among the buried lie Rudolph Valentino’s Doberman, Kabar, along with a lion named Tawney and Hopalong Cassidy’s horse, Topper. Pets belonging to Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart and Alfred Hitchcock are mingled among their brethren. Pet obituaries were published regularly in newspapers.

The Jones family owned and operated the facility for more than 40 years. In 1973, the family donated the property to the Los Angeles Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (S.P.C.A.), but after 10 years, the S.P.C.A. considered selling the property to local developers. Before that could happen, in stepped a nonprofit public benefit corporation dedicated to the preservation of this special sanctuary.

On September 12, 1986, the organization Save Our Pets History in Eternity (S.O.P.H.I.E.) closed escrow and dedicated the L.A. Pet Memorial Park into perpetuity. Because a privately held pet cemetery cannot be considered for 501(c)(3) status, current Board of Directors president, Shera Danesse Falk (Mrs. Peter Falk) and a group of nine board members oversee a group of approximately 500 members who personally contribute annually to keep the cemetery funded.

Today, a dedicated staff of seven makes sure the property is well-maintained and properly supportive of both pets and their human caretakers.

Client Relations Representative Marie Beavers is the first face you see through your tears and confusion. She worked in human cemeteries for 17 years, but quickly discovered that to most, the burial of a beloved pet oftentimes seems unreal and difficult to discuss with others. Pet grief has no time limit and each person needs to work through his or her sadness in their own personal way. Beavers points out that in comparison to a human passing, pet owners proudly pull out pictures of their best friends.

“My question to myself is how can I help them through this process,” Beavers says.

There is no schooling for this type of work, employees say. Whitney feels much of his work ethic “comes from the heart and experiences of the past. Pet people can see a phony a mile away.”