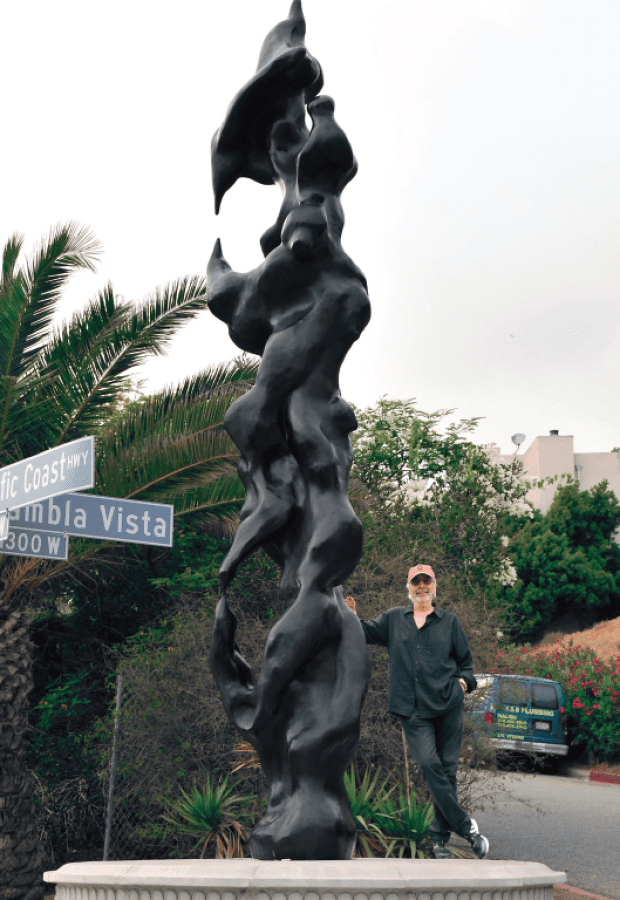

If you’ve noticed a 17-foot-high addition to the Malibu landscape embedded in the fountain at the corner of Pacific Coast Highway and Rambla Vista, you can thank an artist more readily known for his eight Grammy Awards, 14 Platinum albums (and 15 Gold), one of the most successful recording labels of the past 25 years, Billboard Hot 100 dominance and perhaps the most scandalous album cover of 1965 (which had a lot to do with whipped cream).

Trumpeter and Malibu resident Herb Alpert’s recent loan to Malibu’s public art collection is titled “Freedom,” and is an example of the musician’s quieter artistic side. The black bronze sculpture is inspired by totems of the Northwest Native Americans and pays homage to the Chumash people who used to populate Malibu shores.

“The Chumash didn’t really do totems,” Alpert said in discussing his work. “But there are a lot of birdlike references in this totem that were part of Chumash culture, like pelicans and seagulls. And they represent freedom.”

Alpert doesn’t really enjoy talking about what his art is supposed to represent. He believes the viewer should just drink it in and see if it touches the soul. He feels the same about his music.

“Music—and all art, really—resonates in the soul,” Alpert said. “When you see something that touches you, you can’t describe it. How can you analyze a solo by Louis Armstrong? It’s the feeling you want.”

Feeling is what hooked Alpert resolutely to music when he was a youth. During a teenage orchestral performance of Mussorgsky’s “Pictures From an Exhibition,” Alpert said he became so engrossed in the beauty and majesty of the piece that he literally forgot to come in with his trumpet portion on cue.

His forays into visual art began after his establishment as one of the 20th century’s more prolific and successful musicians and bandleaders. He started painting more than 40 years ago, but said that his first attempts were more like “a monkey pushing a brush around.”

Gradually, images started to flow and he would “riff” on whatever came to mind in abstract freeform. More recently, he began a series inspired by his daughter’s love of organic foods and started to incorporate coffee – grounds and liquid – into his paintings.

He began sculpting some 30 years ago and, like painting, he worked to acquire technique before he could trust his vision to guide his hands.

“Somehow, my mind just captures beautiful images,” Alpert said. “It’s just that mysterious thing.”

Alpert’s painting and sculpture are currently on view at the Robert Berman Gallery in Bergamot Station in Santa Monica (till July 20th). While his canvases sometimes have the sepia-toned look of a Lascaux cave painting, his sculptures are powerful, elemental testaments, in many ways comparable to the raw musculature of a Rodin sculpture (to whom Alpert attributes influence).

Alpert doesn’t mind the comparison.

“There’s a hand-off between all artists and musicians,” he said. “Good composers don’t imitate, they steal.”

Alpert said that when he once complimented the late Stan Getz on a particularly compelling riff, Getz replied, “Oh, I got that from Al Cohn.”

But Alpert said the inspiration for his painting, sculpture and music all come from the same place.

“It must be passionate to be authentic,” he said. “When I first started sculpture, I was just having fun. I didn’t put pressure on myself to create ‘art.’ I just let myself express feeling.”

Apparently, he hit his stride. There are many examples at the Berman Gallery of Alpert’s maquettes, or studies, for his eventual bronzes. Lined up on a display shelf in the gallery, it is almost like viewing an ancient alter to distant deities. His sculpting starts small – a few inches of wax or clay transformed to a small totem and gradually work their way upward.

“It’s hard to say how I choose which piece to cast as a larger bronze,” Alpert said. “ Some of those little pieces just look monumental.”

Whatever the impetus, Alpert’s black totems are finding homes in public squares across the country. They are currently on display at the California Institute of the Arts, the American Jewish University, the West Hills Community Center, and, next year, in Dante Park across from Lincoln Center in New York.

They also stand as sentinels at the Herb Alpert Educational Village in Santa Monica, where Alpert’s foundation has funded an educational center striving to provide equity for underserved and at-risk youth.

To Alpert, arts education is an essential component of a comprehensive curriculum.

“How can the arts not be a part of a complete education?” he asked. “Music teaches you discipline and that spills over into academics. You don’t just pick up a trumpet and play.”

Alpert’s lifelong dedication to discipline has paid off for him. He recently was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Obama and is appearing this week at the Hollywood Bowl with his wife, Lani Hall. His syncopated cover of Irving Berlin’s “Puttin’ on the Ritz” was the highlight of a recent episode of “So You Think You Can Dance,” in an astonishing, three-minute, one-take extravaganza.

“I don’t have a goal when I do a sculpture,” Alpert said. “I’m looking for form. A mystical art form.”

More information on Herb Alpert’s exhibition, “in-ter-course,” may be found at www.robertbermangallery.com.