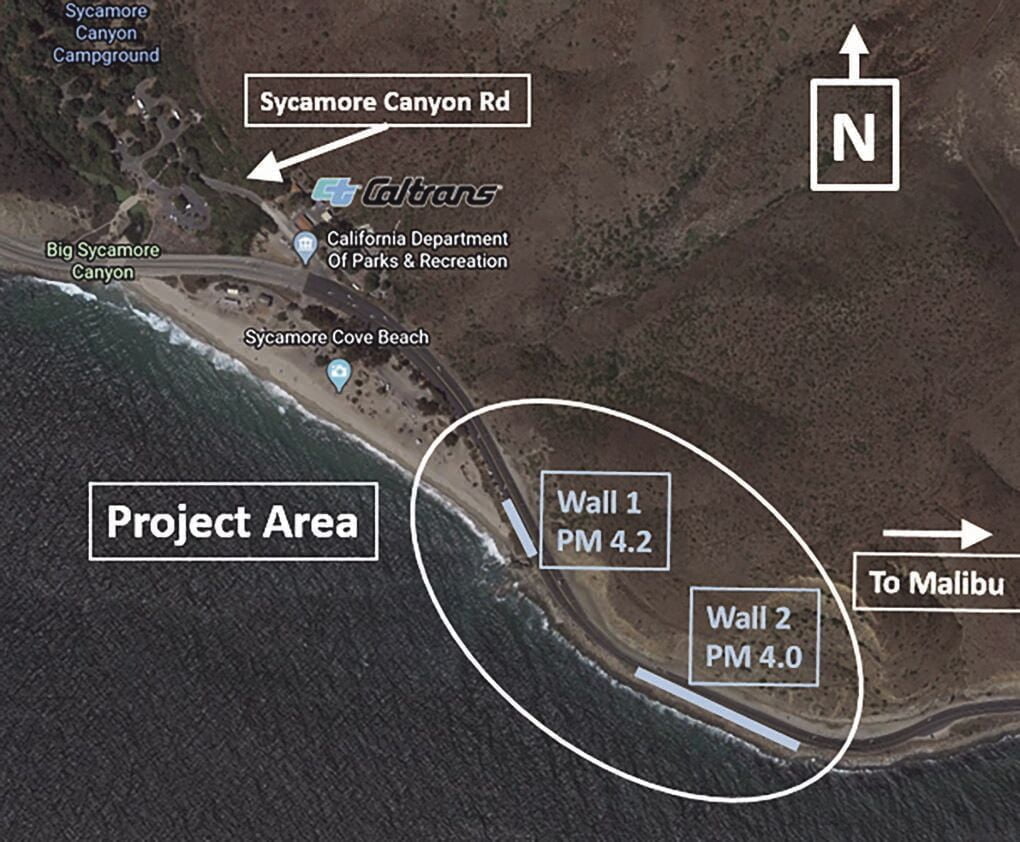

One of Southern California’s most “highly vulnerable” roadways is getting a new line of defense, thanks to a $51 million project now being undertaken by Caltrans along a 1,000-foot stretch of Pacific Coast Highway in Ventura County east of Sycamore Canyon Cove.

The project, which will see the installation of two new “secant” (retaining) walls on the ocean side of the highway, received approval from the California Coastal Commission (CCC) this spring and was expected to break ground on Monday, Sept. 20, and last about a year-and-a-half. During the construction period, the road shoulder would be inaccessible and traffic would be slowed to 25 miles per hour.

When asked whether the 25 m.p.h. limit would be in place 24 hours a day, seven days a week over the course of the project, Caltrans Public Information Officer Jim Medina said yes, and reiterated that the stretch of road to be affected measures just 1,000 feet.

“Because it’s going to be a shared road with bicyclists, it’s a public safety measure for people to be aware and slow down—not only for bicyclists, but for workers and just for safety for everybody,” Medina said.

“Construction will occur day and night as needed, Monday through Saturday,” a Caltrans press release stated.

The work is part of a larger project approved by the coastal commission at its Thursday, May 15, meeting, including additional parking spaces in the Sycamore Cove State Park parking lot and restriping of the highway. The project will also keep K-rail and chin-link fences in place to protect vehicles and pedestrians from falling rocks due to slope erosion, but in many places would widen the shoulder up to four feet to make more room for bicyclists.

At the May meeting, CCC senior transportation program analyst Wes Horn detailed the ongoing erosion in the area and said sea level rise was predicted to have increasingly destructive effects on the roadway.

According to Horn, such projects—“critical infrastructure projects” that have “long design life, low adaptive capacity and the high consequences associated with its failure”—must be studied under “extreme risk aversion” sea level rise projections. In other words, they should be expected to survive 100 years in the most “extreme risk” projections.

The project was expected to last 75 years under “medium risk aversion” projections, so the commission voted that Caltrans and the commission must work on a longer-term solution that will go into place after 30 years, in 2051.

The roadway is considered “necessary to protect the continued use of PCH as a means for access to public beaches, public campgrounds, and nearby communities, such as Oxnard and Malibu, as well as emergency evacuation in the event of earthquake, tsunami, or wildfire,” a staff report from the meeting described. The road is part of a larger corridor management plan, which includes sea level rise analysis and a focus on accessability, according to Tami Grove, statewide transportation program manager for the coastal commission.

“This is going to be one of the most challenging and difficult adaptation plans for the state,” CCC Executive Director Jack Ainsworth said.

The wall project will result in a net loss of about seven parking spaces; however, Caltrans pledged to remove some “No Parking” signs along the highway, resulting in the addition of an estimated 20 parking spots.

When asked about the view from the roadway, Medina said any impact would be minimal.

“There’s a possibility the top of the walls may be visible from the roadway, but it just depends on how the project plays out,” Medina said. “The wall itself is not visible—mostly it won’t be visible from the roadway.”