When the buried city of Pompeii was rediscovered during the 18th century, it sparked an international fascination. Artists began creating works imagining how people lived in the ancient Roman town before it was destroyed, yet preserved, by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79. The works of art depicted a decadent lifestyle, the apocalyptic eruption and its more modern rediscovery and excavation. The re-imaginings came in a variety of forms—from paintings to sculpture and literature to opera.

The Getty Villa’s exhibit “The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection,” which closes Jan. 7, examines the influence of Pompeii and its destruction on the modern imagination. Rather than looking at the archaeology of the city, as many exhibits have done before, the collection turns its lens on the modern fascination with the ancient culture.

“For this exhibition we carefully selected items that weren’t merely Pompeian in theme or subject, but variously reflected a modern interpretation or adaption of the Pompeian legacy to suit contemporary needs,” Kenneth Lapatin, associate curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, said. “Thus we like to say that the exhibition presents Pompeii not, as is typical, as a window to the past, but as a mirror of the present.”

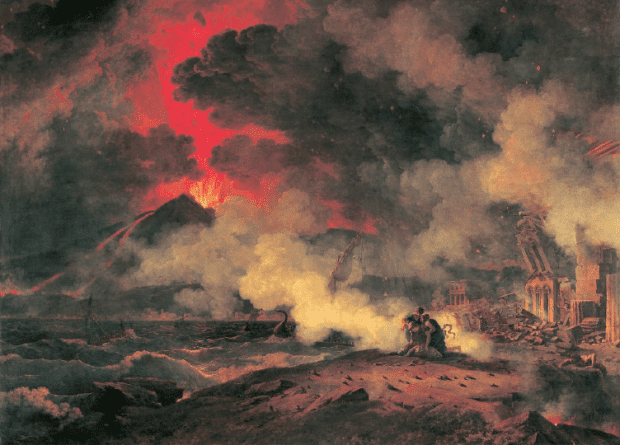

The only surviving eye-witness accounts of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius come in letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus, written about 25 years after the catastrophe. The letters inspired many of the artists who created art depicting the rise and fall of Pompeii.

However, the melodramatic historical novel “The Last Days of Pompeii,” from which the exhibit gets its name, inspired the greatest number of works of art. The novel, written by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, was first published in 1834 and serves as a springboard for much of the art featured in the exhibit. The story depicts Pompeii as a brutal, luxurious and immoral Roman society.

The exhibit is divided into three stages—decadence, apocalypse and resurrection. The categories represent the three significant concepts that moderns have imposed on Pompeii’s past.

“Pompeii was not any more decadent than anywhere else,” Lapatin said. “Its destruction is the climax of any Pompeian narrative; and its resurrection continues to fascinate us.”

“The Last Days of Pompeii” exhibit begins with depictions of Pompeian decadence, featuring paintings illustrating a lavish ancient lifestyle. The notion of Pompeian decadence is tied to the idea that the destructive eruption was a deserved punishment for sin. From ancient frescoes to modern images by Salvador Dali, the exhibit suggests that the idea of this self-indulgent luxury has occupied minds for centuries.

Following Pompeian decadence comes apocalypse, a collection of images portraying the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius and its destruction of Pompeii. The idea of apocalypse entertains the notion that the city existed to be destroyed, and the event has become the archetype for later disasters. The artwork evokes the concept of the sublime, or the frightening, yet beautiful, powers of nature.

After being lost for nearly 1,700 years after the eruption, Pompeii was rediscovered. This event is the focus of the exhibit’s final stage, resurrection. While the Pompeian lifestyle was romanticized in art, so too are the images illustrating its rediscovery. The art of the final stage is emblematic of the modern obsession with rediscovering lost cities and making them come to life once again. Artifacts discovered during excavations are also on display at the exhibit.

Over the past three centuries, excavations and recreations have been taking place in Pompeii, and its rediscovery is credited with sparking the birth and development of archaeology. Today, Pompeii is one of the best-preserved ancient sites. Located near modern Naples, the site draws about 2.5 million visitors each year.

“Part of the appeal of Pompeii, I think, is the brush with death,” Lapatin explained. “The frisson of being in a place that was so suddenly destroyed and thinking, ‘How would I have reacted?’ ‘What would I have done in order to survive?’”

The artistic depictions of Pompeii, its destruction and subsequent rediscovery are vast and varied. From sculpture to literature, some works were closer to history, while others opted for more colorful re-imaginings. Through the artworks on display, “The Last Days of Pompeii” illustrates modern fantasies of Pompeii’s ancient society.

“Sunday we visited Pompeii,” German writer Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe penned in 1787. “Many disasters have befallen the world, but few have brought so much joy to posterity.”

“The Last Days of Pompeii” is on display at the Getty Villa, at 17985 Pacific Coast Highway, until Jan. 7. It is a joint project between the Getty and the Cleveland Museum of Art. For more information, visit getty.edu/art/exhibitions/pompeii