During its monthly meeting, the California Coastal Commission discussed a decades-old blocked public pathway preventing access to the western end of Latigo Beach. On Feb. 13, the commission agreed on a settlement with the respondent, Tivoli Cove Homeowners Association (HOA), to restore public access to the beach.

As part of the settlement, the HOA, which has owned the 104-unit Tivoli Cove Malibu Condominiums and surrounding property since 1989, has agreed to install public access amenities such as a shower, drinking fountain, two benches and signage, as well as widen the public pathway from four feet to five feet. The HOA has also agreed to clean up debris present on the beach. Additionally, the HOA is expected to pay a $925,000 fee as a penalty for decades-long violations of a 1978 Coastal Development Permit (CDP) for the property.

During the meeting, California Coastal Commission Chief of Enforcement Lisa Haage said the respondent “worked closely and collaboratively” with the coastal commission in the months preceding the February meeting.

“We are pleased to announce [the] respondent, the Tivoli Cove Homeowners Association, has worked with our staff to reach an amicable resolution to this case,” Haage said.

Coastal Commission Vice Chair Donne Brownsey said that, while she was pleased the respondent was cooperating with the commission, she still felt that “this is a very egregious violation.”

“There were intentional efforts by the property owner to restrict access and to not comply with the coastal permit conditions,” Brownsey said.

Rob Moddelmog, the commission’s statewide enforcement analyst, presented on parts of the property built decades ago, before CDPs were required: a revetment, or sea wall made up of stacked boulders, and wastewater treatment plant above the revetment.

“Unfortunately, this revetment, wastewater treatment plant and 104-unit condo complex was one of the last projects to be built without having to comply with the new Coastal Act protections for public access,” Moddelmog said.

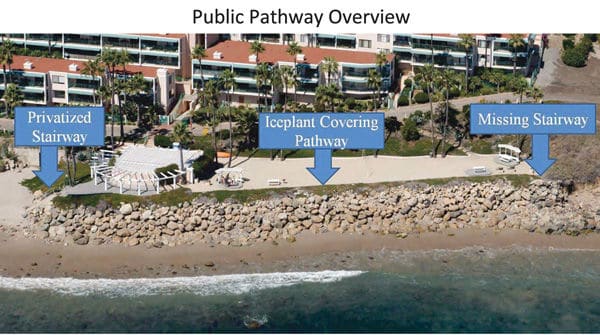

The commission-required public access stairways are supposed to be on the opposite ends of the revetment, according to Moddelmog. The eastern stairway has not been repaired or maintained, and the western stairway was privatized by the HOA for exclusive use by its members and not the public. As part of the settlement, the association has agreed to rebuild and maintain the eastern stairway.

Unpermitted signs were also installed by the HOA deterring public access to the western stairway, stating, “Right to pass by permission, and subject to control by owner.” The signs were not removed until 2018, despite a Notice of Violation letter sent by the commission in 2017.

“Our staff has confirmed that the Tivoli Cove Homeowners Association (HOA) … has failed to provide the required stairs and signed walkway in the dedicated public access area along 26665 Seagull Way, and therefore the HOA, is in non-compliance with the final terms and conditions set forth in [the CDP],” the commission’s letter states.

Stanley Lamport, speaking on behalf of the HOA, said the association supported adoption of the staff’s recommendation.

“The association has agreed not to contest the findings that the commission made for issuance of the Cease and Desist Order, and we’re not doing so now,” Lamport said. “It’s always difficult to watch and not wanna say, ‘We’re not terrible people’ in the process. When the issue was brought to the association’s attention, we promptly came to the commission and said ‘How do we resolve it?’”

A previous property owner applied for the 1978 CDP in order to restructure the on-site wastewater treatment plant. While issuing the CDP, the commission included conditions related to public access.

“In the 1978 permit, the commission recognized the negative impacts of the revetment on public access and required a number of conditions to mitigate for that loss, including the requirement that the property owner provide a public pathway up and over it, so that the public could still reach the beach on the other side,” Moddelmog said. “However, the respondent has failed to provide that pathway and also has failed to maintain the revetment.”

According to the Coastal Act, the commission can impose “administrative civil penalty” fees up to $11,250 a day for each violation, but penalties cannot be imposed for more than five years.

“Commission staff has discovered records that state that the eastern stairway of the public pathway was missing by 1986, and has yet to be replaced,” according to a staff report prepared for the February meeting.

If the $11,250 per day fee were collected for the entire five-year statutory period, the commission could have collected more than $20 million in violation fees. The staff report cites the HOA’s willingness to “amicably resolve this matter” and “provide public amenities in perpetuity” as reasons for a “significant but not extreme” penalty fee.

“Taking all of this into account for calculating the penalty amount, the immediacy with which respondent has most recently agreed to comply with the Coastal Act and engage in the resolution process weighs towards a reduction from a more substantial penalty allowed under the statute,” the staff report states.

Boulders, concrete blocks and other debris block access on the eastern end of the beach. The blocks are likely leftover from an early 20th century Pacific Coast Highway alignment, according to Haage. Other debris, results of the lack of revetment and eastern stairway maintenance, have washed up on the nearby beach, blocking access there, Moddelmog said.

During public comment, MRCA Project Analyst Mario Sandoval spoke in support of penalizing violations of public access.

“We are encouraged by your staff’s efforts to enforce ongoing violations and apply penalties or fees when deemed appropriate whenever public has been denied or encroached upon. The enforcement of the coastal access violations is paramount to fulfilling the mandate of the Coastal Act,” Sandoval said.

The respondent has agreed to clean up all debris, and is required to submit a detailed removal plan within 60 days, according to Haage. A completion plan is also required after all requirements are fulfilled. A penalty fee of $1,000 a day will be imposed if the respondent fails to complete the requirements within the commission’s required deadlines.