Wayne Thiebaud, master printmaker, lithographer, painter, graphic designer and doodler, so disliked being saddled with a label like Pop Art, he switched focus to works that elegantly and expansively highlighted his extraordinary gifts as a “realist working in the grand tradition of representational art,” and turned to printmaking.

“Wayne Thiebaud: Works on Paper, 1948-2004,” which just opened at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine, offers plenty of examples of the works for which he was hailed as an early master of the Pop Art movement of the 1960s. It also forays into woodblock printing, lithographs, serigraphs and an early self-portrait filled with energy and homage to Picasso.

The show, curated by museum Director Michael Zakian, is the third Thiebaud exhibition at the Weisman, underscoring its “special relationship” with the artist.

“What fascinates me about Wayne Thiebaud is his longevity,” Zakian said. “Most artists are lucky to get a good 15 or 20 years. Wayne has been largely in the public spotlight for 50 years now, with a very diverse range of collectors.”

Thiebaud worked as a cartoonist and animator for years before he ever formally studied art. He apprenticed at Walt Disney Studios. He was a cartoonist and filmmaker for the Army Air Force Corps. By the age of 29, he was designing ads for Rexall Drugs.

Degrees from San Jose State University and CSU, Sacramento left him smack in the Abstract Expressionism of the late ’40s and ’50s. But Thiebaud considered himself a realist and created lithos of everyday objects in precisely patterned designs—like an OCD-driven observer of the quotidian life.

A man in black stands silhouetted against a bright storefront window. “Dinner Table” (1956, stone litho) lays out plates, cutlery and wine with precision enough to satisfy the denizens of Downton Abby. “The Marquee” (1950, color litho) uncovers the beauty and liveliness of the rococo patterns in a vintage movie theatre.

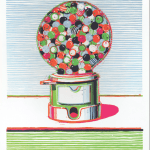

In 1962, Thiebaud debuted his signature paintings depicting everyday American desserts and was recognized as an artist who exemplified, early on, the Pop Art of the Warhol era. Gumball dispensers lined up in a row, ice cream cones, chocolate cakes and pies of every variety were immortalized by Thiebaud, who by many accounts was fascinated with the American preoccupation with food.

Examples on display at the Weisman include drypoint etchings and color lithos like “Neapolitan Pie Portfolio” and “Pie Case.” Thiebaud was intrigued with the cultural image of pie in American vernacular like “pie in the sky,” pie-eating contests and pie-throwing antics in Chaplin films. Apparently, a meringue is not just a meringue.

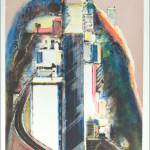

But Thiebuad also brought his extraordinary skills as a graphic artist to bear in striking urban San Francisco landscapes. His vertiginous views of hilly city streets and high-rise buildings like “Down Mariposa Street” (1979, hard ground etching) and “Neighborhood Ridge” (1984, aquatint and drypoint etching) show streets rising almost vertically, and buildings that tower into a skyline dotted with palm trees and tiny, puffy clouds. It’s almost a Seussian perspective that defies laws of linear perspective, but absolutely captures San Francisco imagery.

The exhibit also features several pastoral examples of expanses of the Sacramento River Valley, from perspectives above and at ground level. His paintings of Yosemite, as in “Canyon Ridge” (1991, color monotype) and “Round Ridge” (1977, color monotype), reflect the same intense fascination for the drama of Yosemite’s towering cliffs that Ansel Adams showed photographically.

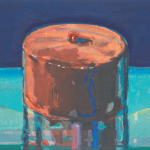

But Thiebaud continued to return to his absorption with orderly renditions of everyday objects. In “Black and White Lipsticks” (1964), “Eight Lipsticks” (1988) and “Paint Cans” (1990), he gently mocks the pretensions of being a fine artist, with the same systematic order he treats shoes, bow ties and toys.

Zakian said Thiebaud’s appeal “ran the gamut, from art professionals to children.

“This is why Wayne is as relevant today as he was decades ago,” Zakian said. “Everyone can find something fascinating. He didn’t follow trends, and he painted what he wanted. He said that with everything he did, he tried to do it well.”

“Wayne Thiebaud: Works on Paper” runs through March 30 at the Weisman. More information, call 310.506.4851 or visit arts.pepperdine.edu/museum.