For a guy who hangs out at the county dump, Joe Sufredini is an amazingly upbeat sort. Part entertainer, part educator, this falconer has the best of several worlds.

The backyard of the Castaic home he shares with his wife Shawna and 1-year-old son Logan has lawn, trees and a kid’s swing set. It also has perches for hawks and falcons and backs up to an undeveloped hillside where the birds train.

Bred in various parts of the country, they’re purchased usually by the age of 2 months-that’s when raptors have reached their adult size and are ready to begin gentling and training.

On an average day in good weather, five or six birds are enjoying the outdoors from perches in the Sufredini backyard. Several more are still in their mew, or hawk house, a kind of small barn with perches where the birds are sheltered at night. One or two may be working at the Castaic Landfill, where they keep the seagulls from foraging in the trash.

We are introduced first to Patula, a hybrid cross between a peregrine and a prairie falcon, two of the fastest birds anywhere. Because she is bred from birds indigenous to the United States, Patula is used only for hunting and doesn’t work in movies.

The Migratory Bird Act makes it unlawful to use indigenous or migratory birds for profit, which includes films, commercials or other entertainment.

“She’ll be hunting about 400 feet high. When you flush a duck or a pheasant, she folds up her wings and goes into a stoop. At 120 to 140 mph, she looks like a torpedo,” Sufredini says. “She knocks it out of the sky, then she binds to it, grabbing it with her talons.”

Usually, the game bird is mercifully stunned or killed when Patula hits, but if not, she dispatches it with her beak.

Resting on a nearby perch is B.B. (short for brown bird), one of the Saker falcons that work at the dump.

“When we first started at the landfill, we had three birds and flew them every 15 minutes,” Sufredini says. “Now we take only one and fly it when we first get there. That’s enough to let the seagulls know a hawk has taken over the territory. Sometimes when they see my truck drive in, they fly back to Castaic Lake. B.B. actually catches gulls sometimes.”

Largest of the birds in the yard is an African Auger hawk named Marshall, a 3-year-old female who came from St. Louis when she was just a baby. Marshall was seen in the Bud Lite commercial that first aired during the Super Bowl and has appeared in films. She steps up onto Sufredini’s hand from her perch, looks at us in a curious way, but seems not to be threatening. She’s much larger than the falcons and has a commanding presence.

“They’re all wild to a degree,” he says “But the amount of time you spend with them pays off in their comfort level. They respond to a whistle to come, and it soothes them when you talk to them. Still, very few birds of prey like to be touched. Their main reinforcement is food.”

The birds are fed rats, mice, farm-raised quail and chicken, mostly frozen, and they have to eat the bones, feathers and viscera to remain healthy.

Sufredini found his calling at age 6 while attending a bird show at the San Diego Zoo.

“This Harris hawk was released from a box and was supposed to land on the trainer’s hand. Instead, it flew down and killed a rat and then flew up on a speaker and proceeded to eat the rat. For about 30 minutes, the trainer had to just stand around and ad lib. I thought it was wonderful.”

The California Department of Fish and Game oversees the certification of falconers, who must find a sponsor, serve a two-year apprenticeship and work five years as a General Falconer before being certified as a Master Falconer. Sufredini is now sponsoring a young trainer, helping him learn how to gentle and train the birds.

“Falconry has been around so long, you really just follow the steps,” Sufredini says. “First they learn to sit on your fist, feeding from the hand, stepping from a perch to your hand, then short hops. It’s about a month before their first flight, if you’re working every day, to where you can trust them.”

Even so, the falcons always wear a radio transmitter that weighs about 5 grams attached to one leg, because their range is so long.

“Two or three miles is nothing to them. They just go over a mountain and they’re gone,” he says. “I lost a falcon about a month ago. It was gone for about two days before I tracked him down in someone’s backyard.”

Actually, the birds make pretty good neighbors-quieter than dogs, easier to keep home than cats and basically not a threat to humans. But there have been a few incidents.

“My Harris hawk weighs only one-and-a-half pounds, but it can take down an 8-pound jack rabbit. It once chased someone’s chicken and a pet parrot,” he says. “We narrowly avoided an ugly situation.”

The birds are transported to the landfill on perches in the back of an enclosed pickup. A lightweight, leather hood covers their eyes.

“They’re high strung, so wearing a hood calms them,” Sufredini says.

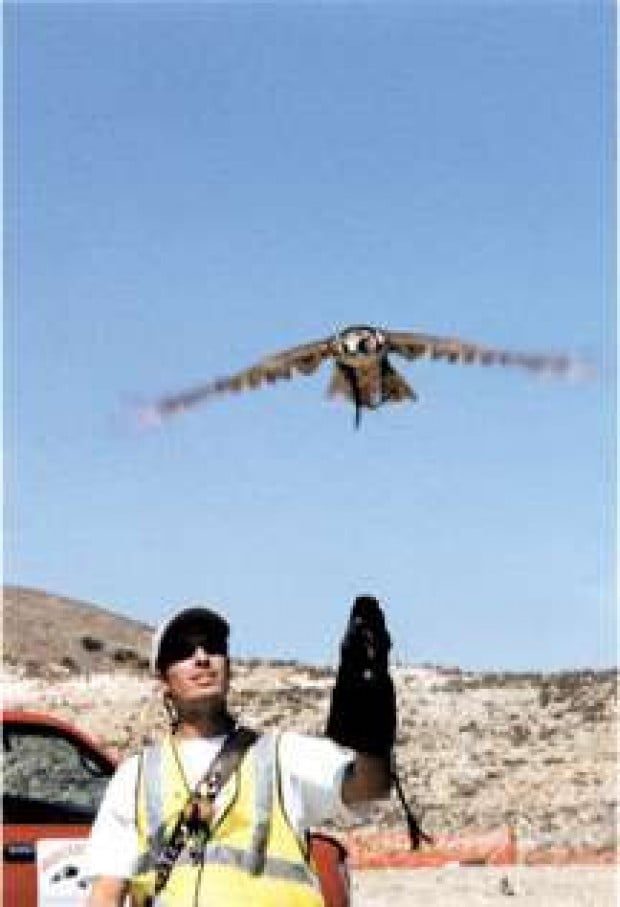

This day, “Squeaker,” a 5-year-old male Saker falcon, is on duty at the Castaic Landfill. He will only make a couple of short flights over the area where huge tractors move and cover the trash. Sufredini calls him back with a whistle and by swinging a lure.

“When I first started, there were 500 gulls, now there are only about 35. In spring, they’re feeding broods of chicks so they’re anxious to get into the garbage. There isn’t much else to eat, so if we keep them out of the landfill, they go back to the beach.”

With his brother, Tony, who is currently working on a film in Africa, they run Avian Entertainment. And while movie work is good, Sufredini has a special interest in education.

“We usually take four different species to schools and talk about the ecological niche each fills, their importance in rodent control.”

He also does some entertaining for children’s parties and has worked with other animals including dogs, cats and great apes, he says.

“But birds of prey are my passion.”

For more about falcons, the Web site is: www.avianent.com