On Feb. 24, The Malibu Times ran a story summing up the California Coastal Commission’s 30-page rejection of a residential construction project on Broad Beach, which had already been approved by the City of Malibu. One of the five reasons the commission rejected the project was, they said, the applicant and city hadn’t used the latest available science on sea level rise.

The trouble is, when the homeowners (the Klein family) applied to the city for their coastal development permit in 2017, they were using the current science. The coastal commission, which didn’t look at the project until 2020, was using data that wasn’t published until November 2018—nearly a year after the city’s approval.

Steve Kent, the Malibu-based architect on the project, took issue with the way the commission handled the entire process.

“Their staff in Ventura stonewalled me, and the coastal commission itself stonewalled us,” he complained in a phone interview with The Malibu Times. “I had a whole presentation prepared for the commission meeting, and they attacked the project and wouldn’t let me talk… It’s very heavy-handed, with no opportunity to note your objections or defend your project—it’s like a communist state. They unilate rally said, ‘Your project is null and void.’

“My understanding is that they’re using this whole sea level rise thing to stop development on the beach, period,” he continued. “They figured out that sea level rise is the way to accomplish their goal.”

Malibu’s Local Coastal Plan (LCP), adopted in 2002, requires structures be designed to last 100 years. Because of that 100-year benchmark, the projects fall into the coastal commission’s guidelines for new developments for very longterm projects, requiring they consider worst-case scenarios for sea level rise.

The Klein’s engineering report from December 2017 assumed 18 inches of sea level rise by 2100 and made all of its calculations about wave action based on that. Coastal engineer Mike Phipps, a contract geologist/coastal consultant for the City of Malibu, approved the number because he thought it complied with California Coastal Commission sea level rise guidelines in effect at the time.

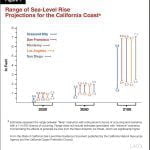

When the project eventually came before the commission in 2020, staff said the project failed to use the most recent, region-specific sea level rise projections published in 2018. They said the new guidelines indicated 66 inches of sea level rise, not the 18 inches used in the Klein’s 2017 report, writing, “The difference is more than 4.65 feet, which is significant in determining the required setback, finished floor elevation, and safety of the proposed structure from extreme events and sea level rise.”

The number used would play a big role in the project’s design when it came to the required setback, finished floor elevation and safety of the proposed structure.

“They apparently expected the project to hit some kind of moving target, because they changed the guidelines after the city approved it,” Phipps said. “You can’t keep upping the standard on a project. They should be allowed to use whatever is in place at the time of the review. The applicant may have spent thousands of dollars on studies based on the old guidelines.”

Kent agreed with that sentiment: “You can’t design your project to a moving guideline—you engineer to the codes that are in force at the time.”

The commission’s 2018 guidelines on sea level rise were adopted from a report from the Ocean Protection Council’s Science Advisory Team, which divides California into 12 geographic coastal regions, specifying low, medium and high-risk scenarios of sea level rise for each. The Legislative Analyst’s’ Office confirms that the state report is using all of the latest science, “Including advances in modeling and improved understanding of the processes that could drive extreme global sea level rise as a result of ice loss from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.”

Phipps said the city updated its numbers when the 2018 report came out and its current standard guideline is four feet of sea level rise in a hundred years, whereas it was nine to 12 inches just a few years ago. “It’s changed dramatically. The science is changing quickly,” he said. The four feet estimate is based on the lowest risk scenario for the Santa Monica area.

It appears the California Coastal Commission made an example out of the Klein project. In its appeal, the commission wrote: “The way this permit is resolved will affect future redevelopment of homes on beachfront lots in the city. This is an important precedent not just for the city, but also statewide.”

Despite these pronouncements, Phipps said the commission still had not come out with specific guidelines for residential projects, even though they were promised a year and a half ago.

The Klein project has another hearing scheduled with the commission, but Kent said it will mean starting all over again, with three years of work down the drain.