Nude and swinging a club, Theodore F. Gedeon (1876-1934) rushed from his cabin early on Saturday morning, July 4, 1931, to terrorize Elkhorn Camp, located one-and-a-half miles up Topanga Canyon, on the edge of the historical Malibu Township.

What happened next made headlines in papers around the region including the Los Angeles Evening Express, The Record, the San Bernardino County Sun and the LA Times.

Around 100 holiday campers woke to his deranged shouting. From a neighboring cabin, S. Keller emerged to pacify him, but was beaten back and received a broken wrist. Those who had been sleeping in tents fled to the hills.

Unable to find another easy victim, Gedeon stopped a car on the road and clubbed the windshield. Glass fell on Edward, Doris and six-year-old Robert Chilcott, who was most badly cut of the three. Edward jumped out and tried to corner the madman, but Gedeon escaped to the highest branch of a tree.

Soon, the authorities arrived: Malibu’s Deputy Constable William Bovett (1901-1963), who lived nearby in the Rodeo Grounds, and Deputy Sheriffs H. A. Berger and Frank Chapman.

The officers first aimed shotguns at Gedeon and threatened to shoot if he didn’t come down, but he ignored them. Chapman then climbed the tree and wrestled the club away from Gedeon. Disarmed, the madman became docile and allowed himself to be taken to the Los Angeles General Hospital for psychiatric evaluation.

Five days earlier, Gedeon had thrown a surprise birthday party for his wife, Pauline (1880-1946), in Santa Monica, where they lived. Afterward, he had suffered a nervous breakdown and she had brought him to Elkhorn Camp to rest. Without sharing the details of his initial breakdown, she explained that he’d had longstanding mental health issues, but that he had never become violent before.

The Elkhorn Camp manager, Francis J. Perry, said Gedeon had shown no signs of insanity until Friday night, July 3, when Perry asked the couple to move to another cabin, perhaps to better accommodate the Fourth of July crowd. Gedeon refused with an irrational anger that kept growing until his relapse.

Gedeon was born into an immigrant community of Sudeten Germans in Cleveland, Ohio, that also produced two Major League Baseball players with his surname: Joe Gedeon (1893-1941) and Elmer Gedeon (1917-1944). Although they weren’t closely related, the association still adds another uneasy dimension to Gedeon’s choice of a weapon—described only as “huge” and “heavy”—and the image of him swinging at people.

Gedeon had worked as a carpenter in Santa Monica since 1921. A short article in the Santa Monica Evening Outlook suggested that he might have been to Elkhorn Camp at least once before, when he organized a family “picnic and barbecue dinner in Topanga canyon” in 1925.

His son, Ted P. Gedeon, owned the popular Ted’s Pioneer Delicatessen on Third Street in Santa Monica in the 1920s and worked for the Douglas Aircraft Company in the 1930s.

Nothing could be learned about Theodore F. Gedeon’s life after his rampage. He died of an undisclosed cause three years later, in 1934.

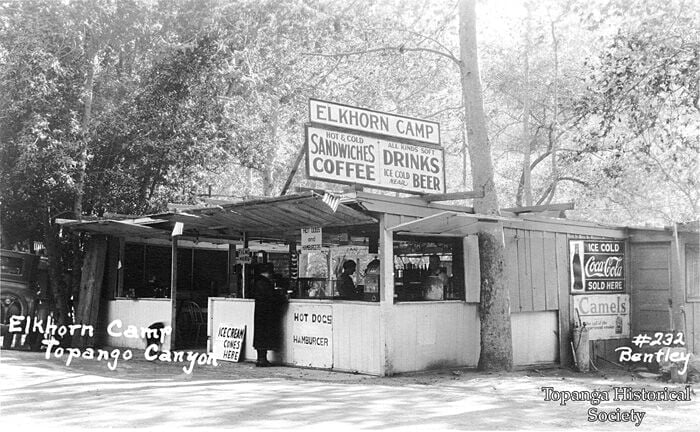

Sadly, this is the only well-documented story about Elkhorn Camp, which changed its name to Perry’s Camp the following year, as if to distance itself from the tragedy. With a cafe, an outdoor dance floor, a lake and a small goldfish pond (“one of the major attractions”), it must have been a wonderful place when there wasn’t a maniac on the loose.

The resort was beloved by newspaper cartoonist Thomas Crawford Hill (1900-1951), who also hailed from Cleveland. Hill came to Los Angeles to animate some of the earliest Mickey Mouse cartoons at Walt Disney Studios. In 1931, he left Disney to open his own animation studio, based around his character Squegee, a pirate who defied stereotype, being “clean and honor inspiring.”

As the Great Depression wore on and Hill’s dream stalled, he was grateful to find a cheap cabin at Elkhorn Camp—where he lived “like a king”—and a chef’s job at his friends’ hamburger restaurant in Hollywood, where he always had food. On the sign of the restaurant, called The Ink Bottle (in reference to his cartooning), he painted his pirate, Squegee.

Hill’s fortune changed when he married a wealthy regular customer, actress Gail Hepburn, and returned to a successful career in newspaper cartooning in 1933. Yet, the pair retained his Topanga cabin for weekends.

Elkhorn Camp burned down in a major wildfire five years later, on Nov. 23, 1938.

Pablo Capra is the archivist for the Topanga Historical Society and author of Topanga Beach: A History (2020). More at topangahistoricalsociety.org.