Long under public scrutiny in Malibu, the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority (MRCA) made headlines in 2019 over a battle with residents of the Sycamore Canyon neighborhood, which resulted in a lawsuit against the MRCA and a counter-suit asking for millions of dollars in fines for homeowners of the private Malibu neighborhood.

A look into MRCA finances reveals the government agency’s financial tactics in its quest to acquire (and thereby conserve) more land in the Santa Monica Mountains area.

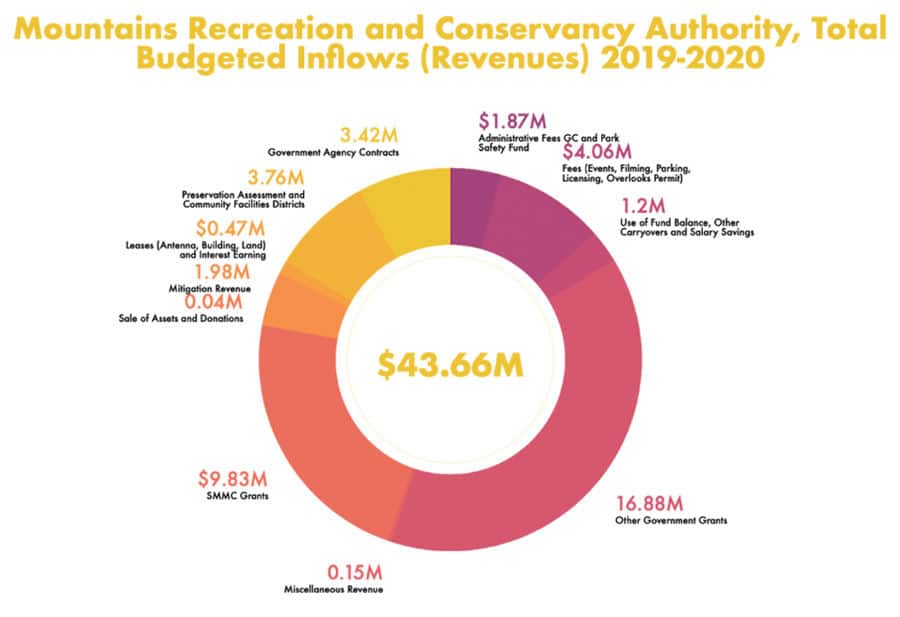

A significant amount of the MRCA’s funding comes from its parent organization, the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy—a state agency tasked with buying private land to turn into protected public spaces. The MRCA (with a total 2019-20 budget of $43.6 million) received $13,069,183 in grants from the conservancy in the 2017-18 fiscal year, nearly a third of its total revenue. These governmental grants came from California voters who voted “Yes” on MRCA-related propositions. The funds are then awarded in grant format, the director of public affairs for the MRCA, Dash Stolarz, explained.

“Bond funds usually go towards acquisition of property, park land or improvements,” Stolarz said. “Improvements could be anything from restrooms to trails.”

Acquisition of land is part of the conservancy’s largest expenditure, land and improvements. Personnel, the second-largest section of expenditures, is allocated to MCRA management and staff; the third largest, operating expenses, is allocated toward ranger services and maintenance of parks, Stolarz said.

The MRCA is also projected to receive over $9 million this year in Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy (SMMC) grants, according to the agency’s 2019-20 budget.

Past audits

The MRCA and SMMC have undergone their share of public scrutiny. In 2004, the LA Times reported on a damning California Department of Finance (DOF) audit that revealed what they described as the conservancy’s systematic mismanagement of bond funds: asserting the conservancy was “funneling away money to pay for legal fees, office expenses, conferences, cars, travel, vacation and sick pay, and ‘excessive’ overhead charges,” according to the article from June 2004.

Perhaps most notable is the DOF’s concern that the SMMC and MRCA are both governed by the same individual—Joseph Edmiston.

The conservancy’s response is that this practice is legal; several lawsuits have demonstrated that this practice is within the conservancy’s legal purview, due to their joint powers agreement.

“[The relationship between the SMMC and MRCA’s governing board] compromises both organizations’ ability to adequately protect the bond funds from waste, abuse or irregularities,” the auditors wrote in the 2004 report.

These allegations have not gone away; in a subsequent 2011 audit, the DOF concluded that while the SMMC had improved some of their accounting practices since the 2004 report, the auditors’ major concern still remained.

“Having the same executives in charge of both organizations (as grantor and grantee) creates independence impairments that can compromise effective oversight of state funds,” the auditors wrote.

Brush clearance

In the wake of the Woolsey Fire, Malibu homeowners have raised concerns over one way the MRCA may be saving a few dollars: issuing mandatory brush clearance that extends well into public land. Homeowners received annual documents from the MRCA that shift financial and legal responsibility for brush cleanup to homeowners.

The document starts by outlining state laws mandating property owners clear brush within 100-200 yards of structures on their property. It then grants permission for homeowners to clean up brush on MRCA land, so long as it is within the 100- to 200-yard perimeter of a property structure.

For example, if a property owner’s house is adjacent to MRCA land, and the house sits 50 feet from the property line, then the owner is responsible for cleaning up the brush on the next 50-150 yards, even if that land is under MRCA jurisdiction.

City of Malibu Fire Safety Liaison Jerry Vandermeulen said this shift in responsibility is not common practice for city governments. Typically, counties will clean up the brush and add compensatory fees to the landowner’s next tax bill. But if a resident’s property abuts MRCA land, that person is held liable for maintaining the 100- to 200-yard brush clearance and, as a result, can face fines—in essence, for not clearing MRCA property.

“If it’s a private property owner, then there are fines […] but because of this state law that basically exempts MRCA, there’s basically no recourse against MRCA if they don’t do anything,” Vandermeulen said.

Fundraising

Another way the MRCA gains revenue is through a 1982 state law known as Mello-Roos that allows local governments to collect special taxes for certain projects—like roads, infrastructure and schools. In order to do this, MRCA submits a request to form a community facilities district (CFD), a pop-up district that votes on these special taxes. If two-thirds of votes cast in the district approve the tax hikes on their ballots, then the taxes get levied in the district. The special taxes are collected in the same manner and time as regular property taxes.

Critics of Mello-Roos laws say the public understanding of these ordinances is limited, and they are subject to gerrymandering. The laws have also withstood years of scrutiny in the courts. Once the taxes are enacted, revenues are held independently from the main budget.

The MRCA has two CFDs: CFD No. 1 consists of areas west of Griffith Park and east of the 405 Freeway, including the Hollywood Hills. CFD No. 2. is comprised of Woodland Hills, Encino and Tarzana.

Stolarz said she manages the community facilities districts. To acquire a new one, Stolarz looks for a willing seller, public sentiment and the funds to purchase the land. The MRCA has been studying land and working with the community to figure out how to buy the land.

Once the MRCA decides the CFD’s boundaries, the board proposes putting the measures on the ballot.

MRCA sold voters on this extra funding by promising to use it to “help protect and maintain local open space, wildlife corridors and parklands and to increase fire prevention, ranger safety patrols, and clean water,” according to the MRCA website.

These special taxes were voted to be in place for 10 years. Currently, property owners in CFD No. 1 pay $59 per parcel; $34 per parcel is paid by property owners in CFD No. 2 every year. (A parcel is a lot within the CFD.)

CFD No. 1 was created after voters approved ballot measure HH in the Nov. 6, 2012, election. The measure levied an annual parcel tax of $24 of developed property for 10 years. The measure received 76.18 percent support.

In the same election, CFD No. 2 was created, and ballot measure MM was passed by 68.67 percent of registered voters in the three cities the district consists of. This charged property owners an annual tax of $19 per parcel.

“They were formed specifically because that is a core area of preservation in the city of Los Angeles,” Stolarz said. “There were a lot of activists who wanted to purchase certain properties that were open space properties that you might be able to get some statewide funding.”

In 2016, additional parcel special taxes were imposed on the two districts. Stolarz said the people wanted more services and more land.

“The first one was very successful, and people wanted more,” Stolarz said. “The second one was just different properties, more patrol and increased maintenance.”

Ballot Measure GG added an annual special tax of $35 per parcel on landowners in CFD No. 1 when voters approved in the Nov. 8, 2016, election with 83.68 percent support. The MRCA also added Ballot Measure FF with a special tax of $15 per parcel in CFD No. 2, which passed with 76.99 percent.

Although these taxes are approved by voters within the districts, The Malibu Times found that the residents reporters spoke to were unfamiliar with the work done by the MRCA. Encino resident Tina Conrad recalled voting for Measure FF in 2016, but said the average citizen will not see the results of these taxes.

“If it’s maintaining wilderness, parks, or stuff like that, you don’t see improvements all the time,” Conrad said. “It takes time and is a long process sometimes.”

Conrad added that the average taxpayer would not know where to look to see what their tax money is being used for. “It’s a trust factor,” she said.

The MRCA maintains that CFDs and the parcel taxes are welcomed by the residents because of the added benefits to residents.

“They are really popular because they increase patrol and maintenance in the areas,” Stolarz said. “People in Hollywood and Woodland Hills, Encino and Tarzana like us a lot and they like the work that we do.”