The Topanga Bubbles is a popular fishing spot about a mile from the beach, where natural gas rises up from the seafloor. Why it attracts fish is a mystery, but one guess is that they like the rocky terrain around the vent.

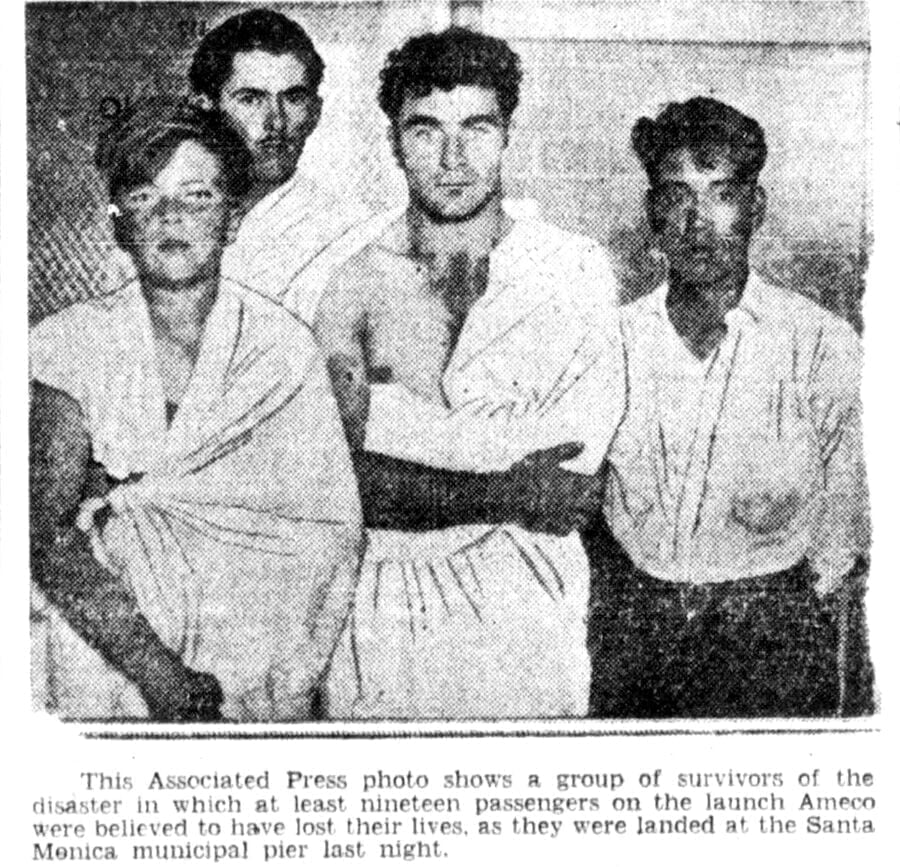

This site is connected to the worst boating accident in the Santa Monica Bay, in which the overcrowded fishing boat Ameco capsized and 16 people drowned on Memorial Day, May 30, 1930.

The trouble started when the 45-foot Ameco left the Santa Monica Pier for its second daily trip to the Topanga Bubbles with an estimated 70 people on board. Half as many would have been crowded.

A fisherman who refused to get on warned the ticket seller, according to the June 3, 1930, edition of the LA Times.

“I told her she was overloading the boat … and she replied that they had to on Sundays and holidays, as they were the only days they had in the week, the others not amounting to anything,” the man recalled to the newspaper.

At the Topanga Bubbles, a wind came up and the sea grew rough.

The inexperienced captain, Bill Lightfoot, 25, raised anchor at 4 p.m. for the return trip and turned the boat parallel to shore. A wave slapped the side and splashed the passengers. As everyone ran to the other side, another wave caught the boat off balance and tipped it over.

“The interlude between merrymaking and deepest tragedy was painted as so brief that it was impossible for anyone even to grasp at a life preserver before being flung into the whipping waves,” the May 31, 1930 Evening Outlook newspaper reported.

Gasoline and oil spilled out of the Ameco, choking the swimmers as they battled the waves. People tried to hang onto the slimy bottom of the boat before it sank. Death appeared be selecting its victims to show different ways of suffering.

Florence Keller, 18, drowned, and her father survived.

Jane Keller, 14, survived, and her father drowned.

Barbara Jones, 16, lost her grandfather while trying to save Robert Buchen, 17. She held the unconscious teen up for 20 minutes, then realized he’d died from a head wound.

There were also uncanny tales of survival.

Robert’s friends—Earl Smith, 17, and Howard Martin, 16—helped others stay afloat and were the last to be saved themselves.

Paul Fowler cut off his heavy shoes with a pocket knife, then stabbed a barrel to make an extra handhold where seven others were already clinging.

One man swam to a fishing barge half a mile away. Another made it to shore.

The loss of life would have been much greater if two other fishing boats hadn’t been nearby, the Freedom and the Palisades. The passengers on the Freedom threatened mutiny if more people were brought on board, but deckhand George King reportedly shouted, “I’ll smack the first man that sets foot in this pilot house!” as Captain Joe Fudge coolly steered through the middle of the swimmers, so they wouldn’t pull his boat over.

A lucky coincidence also saved lives. Scanning the ocean with binoculars, Santa Monica Canyon pharmacist Burton “Doc” Law happened to see the Ameco turn over. He immediately reported it, sending lifeguards racing to the scene. During their rescue work, they placed a marker where the Ameco had sunk, but the waves washed the marker away, and the wreck has never been found.

Only three bodies were recovered that day and since no record was made of the passengers, nobody knew how many were still missing. The radio news brought thousands to the beach seeking answers. Drivers shone their headlights into the surf to aid rescuers. Policemen searched cars that had overstayed in the parking lot.

“Now and then, a man shuffled tiredly into the parking space and fished from a damp pocket a crumpled and brine-soaked ‘ticket,’” a contemporary account published in the LA Times reported. “[He’d] claim his car, try graciously to answer the attendant’s eager question: ‘How did it happen?’—and drive away homeward into the night.”

The Ameco belonged to a small fleet of boats owned by the Morris Pleasure Fishing Company. The Morris family, descended from generations of Nova Scotia sailors, were peculiarly callous to the tragedy.

Captain Clifford Morris refused to fire the Ameco’s captain, Lightfoot.

Less than two weeks after the tragedy, Captain Duncan Morris wrote a letter to the editor of the Evening Outlook opposing the outcry for new laws: “There should be absolutely no attempt by local bodies to interfere with the operator … with ballasting … [or] to pile additional equipment on such boats … [Only to] insure … ‘elbow room at the rail.’”

The Morris Company invited people to fill up their fishing trips while Navy boats, Japanese fishing boats, airplanes, and the Goodyear blimp were still searching for bodies.

“Capt. C. A. Morris brings news that the pier and barges are continuing the run started last week, and that the recent disaster has not stopped the many ‘Izaak Walton’ fans from filling all available space,” the Outlook reported on June 9, 1930.

Yet, these fishing trips inadvertently joined the search by discovering some of the victims. The first body to resurface was Barbara’s grandfather, Ward S. Ferguson, found near the Topanga Bubbles on June 13.

The last of the 16 bodies, and the ones that the Japanese fishing boats had been after, were found on June 23-24, and belonged to Shizuo “Sam” Suyemori and Kiyoki “Joe” Kamimura. A rumor, exoticizing these foreigners, claimed that they had been carrying thousands of dollars in payroll money. This was denied by their friends and family, 11 of whom had been fishing with them, and no such treasure was found in the victims’ wallets.

The Ameco wasn’t the first boat that the Morris Company had lost at the Topanga Bubbles. The 62-foot Kisanto, one of the largest boats for hire in Santa Monica, sank there after its engine caught fire on May 10, 1926. No lives were lost.

It also was not their first boat named Ameco. The original Ameco, 60 feet long, dragged its anchor in a storm on February 13, 1926, and wrecked itself against the Santa Monica Pier.

A string of mishaps that year included the deaths of Captain Thornton Morris and two employees, who drowned trying to save a different boat that got loose in a storm on April 8, 1926.

The Ameco disaster led to new boating regulations on seaworthiness and passenger limits. It also brought up other issues, like that Santa Monicans were poor swimmers, and none of the schools had a swimming pool. Some argued that pleasure boats shouldn’t even be allowed in the Santa Monica Bay because it was really just a “bight,” a shallow indentation in the coastline.

“The word bay deceives many, both on land and sea. It conveys the thought of protection from storms and thundering swells of water. Such protection does not exist here,” the Outlook wrote.

In 1935, the Topanga Bubbles got its own fishing barge, the 350-foot ship Star of Scotland. This ship had experienced an overloading accident as well. Earlier that year off Santa Monica, a stage built for fishermen along its side collapsed, and one man drowned, after people came running to see a boy’s big catch. Captain Charles Arnold was found innocent because the stage met current requirements and an insurance company had inspected it days before.

In 1938, the Star of Scotland was sold to gangster Tony Cornero, who converted it into Santa Monica’s most notorious gambling ship, the Rex. Repurposed again to fight in World War II, the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine near South Africa.

The famous Star of Scotland shipwreck off the Santa Monica Pier is a later ship that Captain Arnold operated as a restaurant until it sank in a 1942 storm. In 1946, he and his wife moved to Topanga and took over the restaurant Schuler’s Grill, where Topanga Living Café is today.

One final event at the Topanga Bubbles is worth noting: an explosion heard there just after dark, on Nov. 25, 1936, and followed by a heavy sea. No wreckage was found, so it probably wasn’t a boat, and no light was seen to support the theory that a meteor had crashed. A sailor nearby believed the explosion had come from underwater and was caused by the bubbling gas.

Pablo Capra is the Archivist for the Topanga Historical Society and author of “Topanga Beach: A History” (2020). More at topangahistoricalsociety.org.